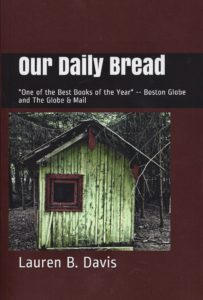

Our Daily Bread

Title: Our Daily Bread

Title: Our Daily BreadBuy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Audible

Published by: HarperCollins Canada

Release Date: January 18, 2018

Pages: 258

ISBN13: 978-1877655722

Synopsis

Robert Benchely’s “Law of Distinction” states: “There are only two kinds of people in the world: those who believe there are two kinds of people in the world, and those who don’t.” Our Daily Bread explores the consequences of group attachment – the “us” versus “them” mentality that arises when a collective identity is stronger than that of the individual self. What moral ambiguities result when we view our neighbors as ‘The Others’, as ‘those people’? This is the conflict between the Erskine Clan, long-shunned by the people of Gideon, who live in secrecy and isolation on North Mountain, and whose bootlegging enterprises are expanding into methamphetamine production; and the God-fearing townspeople of nearby Gideon. For generations the clan’s children have suffered unspeakable acts of rape, child abuse, incest, and psychological torture. The intolerant, self-righteous Gideonites decline to intervene, believing their neighbors to be beyond salvation. “That’s the mountain,” they say. “What do you expect from those people?” Yet in both groups nearly everyone has a secret and nothing is as it seems.

Twenty-one-year old Albert Erskine dreams of a better life and explains to a new teenage friend from the town, Bobby Evans, the meaning of the “man’s code” on the mountain: “You keep your secrets to yourself and you keep your weaknesses a secret and your hurts a secret and your dreams you bury double deep.” Bobby’s eight-year-old sister, Ivy, suffers incessant bullying by her classmates. Her father, Tom Evans, a well-liked local bread delivery man, struggles to keep his troubled marriage together. As rumors and innuendo about the Evans family spread, Ivy seeks refuge in Dorothy Carlisle, an independent-minded widow who runs a local antique store. When Albert ventures down from the mountain and seizes on the Evans’ family crisis as an opportunity to strengthen his friendship with Ivy’s brother Bobby, it sets in motion a chain of events which can only result in unexpected and dire results.

The novel’s tone shifts from humorous to extremely dark because each chapter is told from the differing points of view of the memorable main characters. The writing is smooth and compelling as this complex psychological conflict between the “us” and “them” unfolds. Our Daily Bread is a raw, convincing allegory: the Erskine Clan does not exist solely on North Mountain.

Davis credits her inspiration for her novel to the horror she felt when she learned about the abuse suffered by the children of the Goler clan in Nova Scotia.

US/International Edition

Praise

OUR DAILY BREAD LONGLISTED FOR THE 2012 GILLER PRIZE.

OUR DAILY BREAD has been named as one of the "Very Best Books of 2011" by The Globe & Mail!!

OUR DAILY BREAD has also been chosen one of the "Best Books of the Year" by The Boston Globe (Chosen by Jane Ciabattari)

Jane Ciabattari, past President of the National Book Critics Circle, calls Our Daily Bread "chilling and emotionally authentic."

QUILL & QUIRE

* (Starred Review) OUR DAILY BREAD

Lauren B. Davis; paper 978- 877655722

258 pp., 6 x 9, Wordcraft of Oregon

Oct. Reviewed from advance reading copyWith her new novel, Montreal-born writer Lauren B. Davis, who currently lives in Princeton, New Jersey, has created a powerful, harrowing and deeply unsettling work. It’s the sort of novel that keeps you reading even as your skin crawls and your blood pressure mounts.

The story centers on the town of Gideon, a pious, God-fearing community seething with the dark underbelly common to all such towns. The neighbouring mountain is home to the Erskine clan, a family with a long history of child abuse, neglect, violence, and drug-dealing. The Erskines’ sins are known among the residents of Gideon, but the family is mostly left alone, ostracized and distanced. Twenty-one-year-old Albert Erskine befriends 15-year-old Bobby Evans, the eldest child of Tom and Patty, whose marriage is crumbling. Bobby’s younger sister, Ivy, persecuted and bullied at school, takes refuge with Dorothy Carlisle, who runs an antique store. It is the nature of small communities (and novels) that the characters’ lives and stories overlap and intersect, shaping and being shaped by one another.

From its brutal opening—describing a humiliation Albert endures when he is thought to be snooping on some older family members who are getting into the meth business—Our Daily Bread proceeds like a noose gradually tightening: something terrible is going to happen, and the reader is kept rapt, wondering what the precipitating incident will be. Davis drew inspiration for Our Daily Bread from the story of Nova Scotia’s Goler clan—she acknowledges David Cruise and Alison Griffiths’On South Mountain, which documents the case and the community, as source material—and she uses this background to create a stark, beautiful, sad, and frankly terrifying novel.

Our Daily Bread is finely crafted, with careful attention to characterization, style, and pacing. It succeeds on every level, and will leave readers, much like the book’s characters, devastated and clawing toward the light.

- Robert J. Wiersema, author of the forthcoming memoir Walk Like a Man (Greystone Books)

Backstory

One of the things I’ve been troubled by in the past few years is the increasing polarization I see around me. It pops up in any number of places – religion, politics both local and international, public rhetoric, the media, etc. We don’t have to look far for examples – perhaps no farther than our towns, our neighbors, or even in our own families.

I write to figure out what I think about things and to attempt to find meaning. I try to find metaphors in which to explore my feelings and thoughts on what obsesses me.

Excerpt

“Satan draws the soul to sin by choosing wicked company. ‘Do not be deceived; evil company corrupts good habits.’ Corinthians 15, verse 33. I say to you you shall not suffer yourself to dwell among the wicked, nor shall you permit them to dwell among you, lest you become one of them. You shall cast them out, as you would a wolf among the sheep. Send them out, I say, to live in the wild places of their wickedness, like wolves in the barren mountains. Suffer not the sinners to taint the peaceful valley, where the righteous dwell.” — Reverend Edward Johns, Gideon, Church of Christ Returning, 1794

Near the top of North Mountain a tumbledown shed leaned against an old lightning-struck oak at the edge of a raggedy field. Inside, Albert Erskine bent over a sprouting box and gently, methodically, planted the marijuana seeds he’d soaked last night. He placed each one half an inch deep in the soil-filled paper cups, pushing the seed down with his index finger, the nail black-rimmed. The air, hazy with dust motes, smelled of warm moldy earth mixed with the fertilizer he used in the sprouting mix. The seeds had been perfect, virile, and had given off a good solid crack when he’d tested them on a hot frying pan. Once the seeds were settled in their nest of humus, soil, sand and fertilizer, he’d water them and leave them in the locked shed under a grow-light fueled by a small generator. Later, in a couple of weeks, he’d plant the seedlings out in the field. In the meantime he’d prepare the field with hydrated lime and a little water soluble nitrogen fertilizer.

Growing a good cash crop of marijuana took smarts and Albert was well aware of how smart he was. He knew, too, the power of his physical presence. He would have been called handsome in another place, with the cleft in his chin and the furious shine in his brown eyes. Even as a whip-thin, lock-jawed boy there had been something to notice about Albert, some flash of sinewy grace.

Albert finished up, locked the shed with a bicycle chain and combination lock and headed back to the compound. It was a couple of miles through the woods, up and down and slipping sometimes on the spring-mucky ground, but he didn’t mind. It was quiet out here, except for the song of the cat-bird and the early robin.

Halfway to the compound he skirted around the slope, coming up on an old trailer from the low side so he wouldn’t be as easy to spot. He paused at the edge of a clearing. The uncles, Dan, Lloyd and Ray, were paranoid bastards at the best of times. Albert knew he should just keep clear of whatever they were up to in there, but yesterday his little brother, Jack, told him the uncles had started a cooking operation. Albert couldn’t believe even they would be that stupid; he had to see for himself.

The rusty, partly-yellow trailer tilted on its blocks. The windows were covered with tin foil. The breeze shifted and the scent of something sickly sweet wafted toward him. And something else…ammonia? Jesus. Albert crept to a stand of trees closer to the trailer to get a better look. A small pile of rubbish lay half-hidden under some branches. Used coffee filters. Part of an old car battery. Drain cleaner. Dozens of empty cold remedy packets. If things had been bad on the mountain before, Albert suspected they were about to get worse. Much worse. Meth made everything worse.

“What you doing up here, Bert?”

Albert swung round. At the edge of the tree line, Ray, a shriveled, short man smiled at him over the barrel of a rifle. His teeth were brown stubs, and his close-set eyes glittered with malice. Uncle Ray might not be a big man, but even among the Erskines his temper was legendary. He’d beat his wife, Meg, so bad she had convulsions, and when his son, Billy, didn’t have a black eye, he had a split lip or another missing tooth.

“Just getting my seeds ready for planting.” Albert made sure he kept his voice steady. “Good day for it.”

“Field’s nowhere near here, now is it?” Ray shrugged the rifle closer in on his shoulder.

Behind Albert, the trailer door opened. “What’s this then?” It was Lloyd’s voice. “Ray, now, put that rifle down. Ain’t nothing but Bert.”

Ray did not lower the rifle. “He’s spying on us.”

Although Albert didn’t like the idea of turning his back on Ray, he glanced over his shoulder. Lloyd, his dark hair and beard bleeding together in a shaggy mass, wore a plaid lumber jacket. His jeans drooped below his boulder of a belly. He stretched as though he’d been hunched over something and his back was cramped.

“Hey, Lloyd.”

“That right, Bert?” said Lloyd. “You spying?”

“Just rambling.”

Lloyd spat and stepped down from the trailer’s cinderblock step. “Bullshit.”

Albert stepped to the side so he could keep both men in his sights.

“Don’t take another step,” said Ray.

Lloyd was now within arm’s reach. He scratched his beard. “You know, Bert, you are a mystery. You don’t act like family at all now, do you? Don’t come visiting. Live in your little shack. Course maybe you have your own parties. That it? You have the kids come see you? That’s not hardly sociable, now is it? You got your own little weed-growing business going and we leave you alone with that don’t we? We let you have your way there, ain’t that true?”

“I think I’m generous,” said Albert. “You get your taste.”

Ray laughed. “You’re generous? That’s rich. This is Harold’s fucking mountain, Albert. You breathe because Harold says you breathe.”

“The point is,” said Lloyd,” you live like you don’t want to be an Erskine, and that ain’t right. Makes us think, especially when we find you snaking around like this. Nope. I don’t think Harold’s gonna like this at all.”

“You do what you gotta do, Lloyd, but I’m telling you, nothing good’s gonna come from—”

Lloyd’s fist shot out. Albert crumpled to his knees, gasping for breath. It felt like he’d been hit with a pile driver. He struggled to keep his eyes open and watched Ray’s boot travel in slow motion to his head. He rolled and the kick landed on his shoulder, another landed on his kidney.

Lloyd bent down, put his meaty hand under Albert’s chin and twisted it so they were eye to eye. “Albert, you need to watch yourself, boy. You’re Erskine. You’re family. We take care of family, don’t we, Ray?”

“We sure do.”

Albert heard a zipper and felt something wet and warm spray on his legs. He wrenched his face away from Lloyd, kicked out and squirmed away from the urine stream.

“That’s enough, Ray, put yer pecker away. Now, you get on back to that little shack of yours, Bert, and remember who you are. All right now, say it with me. Erskines don’t . . .”

“Talk,” he croaked.

“And Erskines don’t . . .”

“Leave.”

“Good boy,” said Lloyd, and he pulled Albert to his feet. “Now, get on back where you belong.”

It took half an hour to reach the compound. Albert made his way past the old outhouse. Bastards. One of these days he’d show them. His shoulder and back ached. He smelled Ray’s piss. He slapped at a cloud of gnats. That’s what the Erskines were: a cloud of biting gnats. No matter how you swatted at them, they reformed and came at you again.

A few minutes later he came on the cabin his mother Gloria lived in with whatever man she was shacking up with, and Albert’s brother and sister, Jack and Jill, and Kenny, Jill’s son. Smoke slithered out of the rusty chimney, so somebody was probably inside, but he kept going. Gloria had never been a source of comfort.

He veered toward the back of Harold and Fat Felicity’s tin-roofed gray-sided three-room main house on which the compound centered. Harold and Felicity’s grown children, simple-minded Sonny, Carrie and Carrie’s son, Little Joe, lived there, too, as did an ever-revolving stream of uncles and cousins and other assorted Erskine flotsam. A pair of shutters hung on one of the windows. The shutters and the door had once been painted red, but all were faded and peeled now, as much gray as red. The top half of the door held three panes of glass and one of plywood. There were no curtains on the windows, and under the porch canopy rested a spring-sprung couch. Next to the house sprawled a pile of garbage: disposable diapers; plastic bags which rose up in the wind and festooned the trees, hanging on the branches like pale shredded skin; empty bottles of various kinds, some soda, but mostly beer, wine and bourbon; used sanitary napkins; a stained and swollen mattress; the twisted wheel of a bicycle, the spokes sharp and defensive-looking; a small refrigerator Uncle Dan had dragged home from the dump thinking he could fix, but with which he’d become bored after a day and there it lay on its side, its door gaping; various household objects—a bent spoon, a broken cup and three plates, an old brown-stained pillow where mice now nested; two shoes, not matching.

Scanning the house for signs of life, Albert caught a glimpse of Sonny in the front window, waving. He waved back and Sonny smiled and picked his nose. Albert crossed the dirt and ignored Grunter III, the huge brown and tan mongrel who crawled out from under the house and sidestepped over to him, wanting a scratch behind the ears, but fearing a kick. A sympathetic desire, perhaps, but Albert was in no mood.

Six-year old club-footed Brenda, one of Lloyd’s kids, stood on an old bucket and looked in a back window. She wore a boy’s jacket over a filthy pink nightgown, and a pair of rubber boots several sizes too large, to accommodate her twisted left foot. She’d been in need of a bath several weeks ago. Albert knew what she was probably seeing in there, and he knew if she got caught she’d get a worse beating than he just got. If he called out he’d just scare her and she’d make a noise and then they’d both be in for it. He should just walk away and let whatever was going to happen go right on and happen. Erskine’s don’t talk, and Erskine’s don’t leave, and Erskine’s better mind their own fucking business. She turned then, and looked at him, tears pouring down her face.

Brenda watched him come near, wiped her nose with her palm and then turned back to the window. Albert put his hand on her shoulder, and his head next to hers. The window was smoky with grime. Inside, a bare bulb hung from the ceiling. Dan sat on the side of the bed, wearing only a stained undershirt. His head was tilted back, his eyes were closed and his mouth was open and slack. Between his legs knelt Brenda’s little brother, Frank. Dan cupped the boy’s head and moved it back and forth. The child’s hands flailed weakly.

Time peeled away, fled backwards and Albert was six years old again, his mouth full, gagging, the stench and the sound of moans, his own flesh tearing . . . bile rushed acidly into his mouth. His hands shook. His knees shook. He turned away. Spit. Spit again. One of these days, he was going to do it. He’d get his rifle and put an end to the Erskines, all of them.

“Down,” Brenda said.

Albert lifted her off the bucket and watched her hobble off into the woods. He stomped across the yard, passing the plywood-covered well, and as he did he looked back at the front of the house. Old Harold stood on the tilting porch. He wore the same stained and smudged grey overalls he always wore, and the same John Deere cap. He was a big man, with a barrel chest, and if his arms were oddly short, they were thick with muscle, even though Old Harold had to be in his seventies. White stubble showed on his sagging features and his bulbous red nose was an explosion of broken blood vessels. His small, deep-set eyes—wolfish and keen—tracked Albert across the dirt.

“You come visiting, Bert?”

“Just heading back to mine,” said Albert.

“That’s not very sociable. Not right for relations to keep so distant. Come on in.”

“Not today,” said Albert.

“Be seeing you then. I’m watching you, boy.”

Albert felt Old Harold’s eyes on him until he ducked into the tree line and walked the short, but crucial, distance to his own place.

Three years ago, Albert had built a sparsely insulated, one-door, two-window cabin from materials liberated from building sites and scrounged from junk yards. The roof was lower by a good foot and a half on one side, no running water and no electricity, but it kept the rain off and mostly it kept out the cold. He pulled the string with the key on it from around his neck and unlocked the padlock. Inside, he tossed a log into the black potbelly and jostled the log to make sure it caught on the embers. When he was sure it blazed, he flopped down on the mouse-chewed brown corduroy couch that folded out into a bed. Photos of naked women, some astride motorcycles, papered the walls. On the floor were boxes of books and a stack of tattered paperbacks – Lord of the Rings, Catcher in the Rye, Tom Sawyer, Lord of the Flies. A sink drained through a pipe directly into a pile of gravel a few feet from the cabin, and over the sink was a shelf with a few canned goods, crackers and a box of corn flakes.

Albert reached under the couch for a half-full bottle of Jack Daniels, and drank. Good liquor from Wilton’s Groceries and enough in the locked trunk under the window to last a man for weeks if he wanted it to last that long. No, it might not be much of a place, but it was his—a place where he was his own man. Albert drank again, wincing as the fiery liquor seared into a canker on the side of his tongue. He ran his hand down his stomach. Hard as a washboard. His arms were cut, baby, cut. He wasn’t going to be another of the fat fucks up here. Two hundred push-ups every morning. One hundred chin-ups on a tree branch out back, rain or shine, winter or summer. Bring it on. Just bring it on.

He smelled the piss on his pants. “Shit,” he said. He crossed the room and lifted the lid on a steel bucket in the sink. It was three-quarters full of water. It would do. He used his knife to shave slivers off the bar of soap on the counter, stripped off his pants and dumped them in the bucket.

Half an hour later there was a knock on the door. Not loud. A small, safe knock.

“Come on,” he said.

Ten-year-old Toots shuffled in wearing a too-big duffle coat, her sullen, sharp-featured little face hidden behind a curtain of greasy hair, her skinny legs bare and scratched above the rubber boots.

“Put some pants on, will ya,” she said, not moving too far from the door.

“Just washing mine out, don’t worry.” From where he sat on the couch Albert leaned over and pulled a pair of sweat pants from a small pile of clothes on the floor. As he was putting them on he said, “Dan’s got hold of Frank.”

“Yeah, I know. I won the mailbox race today. Felicity said I could run for Brenda, too.”

The mailbox race—first kid to the mailbox and back won a day without having to be “nice.” Kids learned to run awful fast. Albert could have won a fucking gold medal for sprinting.

“You run fast,” said Albert. He sat back down on the fold-out bed and took a long draw from the bottle.

“Harold says you got any booze?”

“That what you’re here for?”

“Harold said I had to come ask you.”

“They drinking down there?”

“You’re drinking, too.”

“So?”

“I’m just saying.” Toots folded her arms with her hands up the sleeves of her coat, scratching her elbows. “What you got to eat?” she said.

He took another swig from the Jack and guilt wriggled into his bloodstream with the booze. He was the oldest of his generation. He should have stolen cans of beans or something—soup or crackers. The younger kids looked to him: Little Joe, Toots, Frank, Griff, Brenda, Cathy, and Kenny. What was less clear was the nature of that responsibility, up here where the view was like heaven and the living was like hell.

He looked at the calendar on the wall, the one with the picture of the earth taken from space. Six days to go until the first of the month and the welfare checks. They’d be down to ketchup soup at the house.

“I got a couple jars of peanut butter.”

“Where?” Toots said, scanning his shelves. “You got any bread?”

Albert got up and went to a wooden box by the back window. He pulled out two jars of extra crunchy peanut butter and turned to the little girl. “No bread, sorry.”

She grabbed the jars and stuffed them under her coat.

“You got no manners? You don’t say ‘thank you’?”

“Yeah, right. Thanks.” She glared at him from beneath her dirty hair. “What about the bottle for The Others?” She used the kids’ name for the adults.

He regarded her, skinny and defiant, practically feral, and so smart. What would she be like, if she’d been raised in some other place? It was a question he asked too often, this great what if? And it was always prodded along by the desire to get the hell out—the great lurching, gut-squalling impulse to grab a couple of kids and run for the city. But a couple? Toots and . . . who? How the fuck could you take a couple and leave the rest? How did you choose? He had no money, no schooling, and no skills. How would they live in the world beyond? Besides, Erskines don’t leave. They were probably all fucking damned anyway. Erskines, for better or worse, stuck together. They’d drilled the code into his head since before he could remember. Nobody talks. Nobody leaves. Seems it didn’t matter how big Albert got, how grown he was, Harold would always be bigger, and meaner.

“Where are the kids?”

“Gone to the woods. Kenny and Frank are inside.”

“Kenny, too, huh? You going to the woods?”

“Can I stay here?

“I’m drinking, too, aren’t I?”

“You’re not much good then, are ya?” She looked at him for the first time and her eyes were razors. “Not when you’re drinking.”

“Smart kid.” He raised the bottle, turned away from her eyes. “Tell Harold to go fuck himself.”

“You tell him,” she said. “I’m going into the woods.”

And she was gone then, like some scrawny forest sprite. She was fast, that one.

“Shit,” he said to the pictures on the walls. Albert considered ignoring the demand, but they might come up and take what they wanted. They’d clean him out if they found his stash, and God only knows what Ray and Lloyd were saying. He took a couple of bottles out of the trunk.

Albert stood in the middle of his cabin. He sure as shit didn’t want to go up to the house, but what choice did he have? He ground his teeth and his knuckles whitened around the bottle necks. Wasn’t there anybody on his side? Surrounded as he was by kin—practically drowning in them—there wasn’t a single person Albert could call ‘friend’.