All's well that ends "well"

I read a novel yesterday by a promising young writer and although I enjoyed it, I was reminded of just how important satisfying endings are. Like openings, endings are tricky. When editors send back a short story or reject a novel, nine times out of ten they’ll say the ending didn’t work for them. It’s also often the first criticism you’ll here from other writers in workshops. Endings need to satisfy. Your closing, it’s been said, caps your story the way a roof caps a house. It’s the last impression and, like first impressions, counts heavily in fiction. If it’s predictable, implausible, trite or saccharine, you’ll disappoint your reader, and a disappointed reader is unlikely to buy another book by you.

The ending must combine the inevitable with the surprising. – Inevitable because readers have lived with the conflicts through all their ups and downs and want them resolved. Surprising because the conflicts should be solved in a way readers cannot entirely have foreseen.

Having an ending resolved, however, doesn’t mean the characters dance off merrily into the sunset, happily ever after. Hollywood, and some commercial fiction, depends on happy endings in which everyone gets what they want, or what they deserve. Although such endings can be lovely — I’m thinking Jane Austen here, who did such a beautiful job of having her characters twirl down the final aisle with grace and humor — such endings are often unbelievable. It is this lack of believability that causes them to be less satisfying than those in which, even if things don’t work out happily, there is a sense the characters are experiencing the true consequences of their actions, either positive or negative. Such consequences can be external — life, death, birth, wealth, poverty, injury, healing; but they must also be internal, they either realize and overcome their mistakes, their flaws, their truths, or they fail to. By this I mean, for example, the alcoholic who may realize they are alcoholic, but chooses in the last paragraph to down a double whiskey anyway. Or, think of that devastating scene at the end of the film, THE WRESTLER, when the title character realizes the consequences of his life-long actions and errors, and takes that final swan-dive from the ropes.

The ending in which the character fails to escape his destiny is perhaps the more difficult for the writer to successfully convey without becoming maudlin. Chekhov was the master of such endings. He once wrote that, “the writer of fiction should not try to solve such questions as those of God, pessimism and so forth.” He thought that what was “obligatory for the artist, is not solving a problem, but stating a problem correctly.”

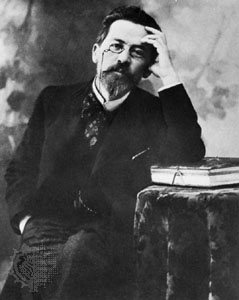

Anton Chekhov -- master of the fictional ending

There’s a terrific article by David Jauss in the March-April issue of The Writer’s Chronicle entitled, Returning characters to Life: Chekhov’s Subversive Endings. It begins this way:

In one of his letters, Chekhov wrote, “When I am finished with my characters, I like to return them to life.” By returning his characters to life, he meant, I believe, something like what David Chase did in the controversial ending of the HBO series The Sopranos: instead of conclusively ending the series by “whacking” Tony, or shipping him off to prison for life, or having him see the error of his ways and turn state’s evidence against his fellow mobsters, Chase simply returned him to his daily routine, essentially as unchanged as the world in which he lives. A great number of Chekhov’s stories end similarly, saying implicitly what the ending of one story says explicitly: “And after that life went on as before.”Whereas previous (and most subsequent) fiction focuses on a climactic change, Chekhov’s stories are frequently less about change than they are about the failure to change. Indeed, as the poet, translator, and scholar Anne Frydman has said, his stories “provide an exhaustive investigation into the reasons for changelessness in human life.”And even when his characters do change, Chekhov’s endings often reveal that their changes either fail to last, merely complicate the existing conflict, or create a new and often greater conflict. In short, Chekhov tends to end his stories by returning his characters to life and the problems created either by their change or their failure to change.

Okay, I’ll admit it — I hated the way The Sopranos ended. Not because Tony was ‘returned to life’ but because I thought my cable had conked out at the crucial moment. I felt it was a cheap trick — and I hate cheap tricks. If he had simply gone on eating with his family and the credits had rolled, I wouldn’t have felt that way and the point would have been made. But I digress — What I find so interesting about Chekhov is the way his world-view found expression in his endings. Chekhov, as this article says, was “deeply skeptical about the possibility of change, especially if that change were permanent and positive, as it so often is in pre-Chekhovian fiction.” Writers write about what obsesses them. They find a way to think about and give voice to the human experience. In Chekhov’s case, as quoted above, he investigated the reasons for “changelessness” in human life. In our society full of addictions and self-destructive behaviors of various sorts, we might learn a great deal from Chekhov’s approach.

Jauss ends his essay this way:

Virginia Woolf has described the effects of these inconclusive endings better, perhaps, than anyone. When we finish a Chekhov story, she says, we feel “as if a tune had stopped short without the expected chords to close it.”But, she goes on to say, the more we become accustomed to his work, the more we are able to hear the subtle music of Chekhov’s meaning and the more the traditional conclusions of fiction—“the general tidying up of the last chapter, the marriage, the death, the statement of values so sonorously trumpeted forth”—all “fade into thin air” and “show like transparencies with a light behind them—gaudy, glaring, superficial.” His endings, she concludes, “never manipulate the evidence so as to produce something fitting, decorous, agreeable to our vanity,”and therefore, “as we read these little stories about nothing at all, the horizon widens; the soul gains an astonishing sense of freedom.” It is my hope that careful study of Chekhov’s endings will similarly free writers and readers of fiction from the constraints of conventional expectations about conclusions.

Free us from the constraints of conventional expectations? Sure, but we must never try to shock for shock’s sake, or manipulate the reader with cheap literary pyrotechnics. Chekhov was, above all else, a brilliant and compassionate witness to the human condition, and his ability to communicate — with simplicity and clarity — what he witnessed is what makes his work so deeply satisfying.