A Refuge for the Broken-Hearted – How is it we were caught?

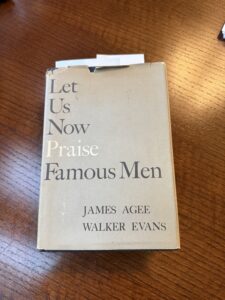

My rather dog-eared copy of “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”

Every morning now, I find myself asking, How is it we were caught? This is a quote from “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” written by James Agee, with photos by Walker Evans, a book that has been my touchstone for the past fifty years (as it was for President Carter, interestingly).

This is what Wikipedia says about it:

”Let Us Now Praise Famous Men grew out of an assignment that Agee and Evans accepted in 1936 to produce a Fortune article on the conditions among sharecropper families in the American South during the Great Depression. It was the time of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” programs designed to help the poorest segments of the society. Agee and Evans spent eight weeks that summer researching their assignment, mainly among three white sharecropping families mired in desperate poverty. They returned with Evans’s portfolio of stark images—of families with gaunt faces, adults and children huddled in bare shacks before dusty yards in the Depression-era nowhere of the deep south—and Agee’s detailed notes.”

When I first read the work, I was stunned. The language, yes. The mad, rushing mix of poetry, the biblical cadence of the prose, the raw, harrowing subject matter… all of that, but something more: Agee’s desperation to make the reader understand. Desperation!

This seems meaningful in 2025. I feel somewhat desperate. Once again, we are living through times that must be documented. We must bear witness. We do not have the privilege of turning away.

Consider pages 75-82 of Agee’s book. On these pages, Agee describes the Gudgers, with whom he was staying, and the world they live in. Part way through the passage, I began to feel that Agee was afraid he would fail us, the readers, and more importantly, he was afraid to fail the Gudgers. Through Agee’s prose, I felt I knew these people — men and women of supreme value, unique, and peerless. Agee was writing as though his very soul depended on bearing proper witness.

The prose begins quietly, elegiacally,

”There are on this hill three such families I would tell you of: the Gudgers, who are sleeping in the next room; and the Woods, whose daughters are Emma and Annie Mae; and besides these, the Ricketts, who live on a little way beyond the woods; and we reach them thus:… Leave this room and go very quietly down the open hall that divides the house, past the bedroom door, and the dog that sleeps outside it, and move on out into the open, the back yard, going up hill: between the tool shed and the end house (the garden is on your left), and turn left at the long low shed that passes for a barn… “

The passage slowly builds, moving farther out across the landscape, and then starts moving closer and closer in, from the land and the town to the minds of the neighbors:

“George Gudger? Where’d you dig HIM up? I haven’t been back out that road in twenty-five years.

Fred Ricketts? Why, that dirty son-of-a-bitch, be BRAGS that he hasn’t bought his family a bar of soup in five year.

Ricketts? They’re a bad lot. They’ve got Miller blood mixed up in them. The children are a bad problem in school.

Why, Ivy Pritchert was one of the worst whores in this whole part of the country: only one that was worse was her own mother. They’re about the lowest trash you can find.”

From there, Agee zooms in again to the dreams and hopes of the people sleeping in the shack. The sentences become shorter, the phrasing blunter, the structure less organized as Agee becomes more and more frantic…until at last words seem to fail him and he breaks into a series of punctuation marks:

(But I am young; and I am young, and strong, and in good health; and I am young and pretty to look at; and I am too young to worry; and so am I, for my mother is kind to me; and we run in the bright air like animals, and our bare feet like plants in the wholesome earth; the natural world is around us like a lake and a wide smile and we are growing: one by one we are becoming stronger, and one by one in the terrible emptiness and the leisure we shall burn and tremble and shake with lust, and one by one we shall loosen ourselves from this place, and shall be married, and it will be different from what we see, for we will be happy and love each other, and keep the house clean, and a good garden, and buy a cultivator, and use a high grade of fertilizer, and we will know how to do things right; it will be very different:) (?:)

How did we get caught?

(? ))% ( (?) ) #*(

Before the era of emojis, these symbols indicated frustration, desperation, and Agee’s rage against his perceived inadequacy.

He goes on:

How were we caught?

What, what it is has happened? What is it has been happening that we are living the way we are?

The children are not the way it seemed they might be:

She is no longer beautiful:

He no longer cares for me, he just takes me when he wants me:

There’s so much work it seems like you never see the end of it:

I’m so hot when I get through cooking a meal it’s more than I can do to sit down to it and eat it:

How is it we were caught?

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain; and when he was set, his disciples came until him:

And he opened his mouth and taught them, saying:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for there’s is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

….

And so on, to the end of the beatitudes. To this day, to the moment of this writing, I cannot read that passage, p. 75-82, without weeping.

What did reading Agee do to me? What does it do to me? For one, it drags me into a world I will never otherwise know and rips open my eyes and heart so that I might see it afresh, saturated with empathy. I cannot live as a sharecropper in the 1930s, but, through Agee’s writing, I experience another person’s reality. Because the work is so well written, I FEEL what these people are feeling, taste their food, smell the stale sheets, feel the cold, hear the barking dogs, and experience the hope and despair. In short, I am made more human, compassionate, and empathetic through my experience of their lives.

Bud Fields and his family (Walker Evans)

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is not a perfect book. Far from it. It is flawed, messy, and meandering, and now when I read it over, I swear I can pick out the moments when Agee’s drinking (which finally killed him at the age of 56 in 1955) gets the better of him and the prose slips into maudlin incoherency. It doesn’t matter. In an article in the Harvard Magazine, Adam Kirsch says, “Suddenly, he [Agee] was no longer writing a magazine article about a socio-economic problem; he was undergoing something very like a spiritual ordeal, in which he was granted a vision of the infinite value of each individual human being, even or especially the poorest.” And he goes on to say, “In Agee’s hands they [the five W’s of journalism] have been transformed into a metaphysical mystery.”

Agee produced far less work, due to his alcoholism, than might have been, but he gave us this marvel of a book. And it is one of the books I feel is most pertinent to our times. We cannot turn away. We must bear witness. And we must ask ourselves, “How is it we were caught?” How have we become ensnared, even complicit, in this terrible time of violence and injustice and fascism and (even more) racism and (even more) misogyny? Bad things are not happening to ‘those people,’ not to some less-than-human ‘other.’ The Gudgers were not ‘those people’ to Agee. They were, and are, us.

How is it we were caught?

Before the era of emojis indeed. All that’s contained in that upper row of symbols unlooked by the shift key. Such a powerful work. And a powerful call to action. Thank you for writing this.

PS Made “your” soup today. Thank you for that too. I’ll share my soup recipe on Monday.