A Refuge for the Broken-Hearted – The Last of the Just

I need to talk about a book I read years ago: The Last of the Just by Andre Schwarz-Bart. I NEED to talk to you about it. I NEED you to pay attention. Please. Please.

The author was the son of a Polish Jewish family murdered by the Nazis. The story follows the “Just Men” of the Levy family over eight centuries. According to Jewish legend, each “Just Man” is a Lamed Vav, who is one of the thirty-six righteous souls whose existence justifies the purpose of humankind to God. Each bears the world’s pains… beginning with the execution of an ancestor in 12th-century York, England, and culminating in the story of a schoolboy, Ernie, the last… executed at Auschwitz.”

Critic Michael Dorris in 1991 described the novel as an enduring classic that reminds us “how easily torn is the precious fabric of civilization, and how destructive are the consequences of dumb hatred — whether a society’s henchmen are permitted to beat an Ernie Levy because he’s Jewish, or because he’s black or gay or Hispanic or homeless.”

Perhaps we can now add to that list… those we would send to concentration camps in El Salvador, maybe even those we tell ourselves we are justified in bombing to bloody tatters.

I HOPE you will read the book. I BEG you to read the book. It doesn’t matter if you’re Jewish or not. I’m not, although my husband is. The novel is rooted in Jewish philosophy and history, but it is a universal story.

But, perhaps you won’t read the book. I get it. Maybe you don’t have time for books right now. Maybe you can’t face it. Okay, so please indulge me here. Because I believe this is so important, I’ve typed the final 4 ½ pages here for you. Surely you can read that much.

Still with me? Thanks. Seriously.

I’ll set the scene — Ernie, the Last of the Just, is in Auschwitz, and knows he is the Last of the Just. He also knows, more than those with him, what is happening, what is about to happen, that it is the end, and that he must do what is right and just to do.

I am so weary that my pen can no longer write. ‘Man, strip off thy garments, cover thy head with ashes, run into the streets and dance, in thy madness…’

One single incident disturbed the ceremony of selection; alerted by the smell, a woman suddenly cried, ‘They kill here,’ which started a brief panic, in the course of which the herd feel back slowly, towards the platforms masked by the strange, floodlit façade, like a theatrical setting for a railway station. The guards went into action immediately, but when the herd was calm again, officers went through the ranks explaining politely — some of them even in unctuous, pastoral voices — that the sturdy men were called up to build houses and roads, and that the remainder would rest after the journey until they could be assigned to domestic or other work. Ernie realized joyfully that Golda herself seemed to grasp at that fiction, and that her features relaxed, suffused with hope. Suddenly the motorized band struck up an old German melody; stunned, Ernie recognized one of those heavily melancholy Lieder that Ilse had been so fond of, and as the brassses glittered in the grey air, another, and secret harmony flowed from the pajama-orchestra out of the music’s languidly glossy tone; for an instant, a brief instant, Ernie also believed deep down that no one could decently play music for the dead, not even such a melody that seemed to come from another world. Then the last brassy note died and, the herd duly gentled, the selection went on.

‘But I’m ill, I can’t walk,’ he murmured in German when, at his turn, the swagger-stick had flicked towards the small group of healthy men granted a reprieve.

Doctor Mengele, Physician-in-Charge at the Auschwitz extermination camp, conceded a brief glance to the ‘Jewish shit’ which had just pronounced those words. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘we shall look after you.’

The swagger-stick made a semi-circle. The two young S.S. men smiled slyly. Staggering with relief, Ernie reached the sad human sea that lapped the edges of the barrack; and with Golda hugging him and the children’s little hands tugging at him, he went in, and they waited. At last, all were assembled. Then, an Unterscharfuehrer invited them, loudly and clearly, to leave their baggage where it was and to proceed to the baths, taking with them only their papers, their valuables, and the minimum necessary for washing. Dozens of questions rose to their lips: should they take underwear? Could they open their bundles? Would their baggage be returned? Would anything be stolen? But the condemned hardly knew what strange force made them hold their tongues, and proceed quickly, without a word or even a look behind them, towards the breach in the ten-foot wall of barbed-wire by the barrack with the grating. At the far end of the square the orchestra suddenly struck up another tune and the first purring of engines was heard, rising into a sky still heavy with morning fog, then disappearing in the distance. Squads of armed S.S. men divided the condemned into groups of a hundred. The corridor of barbed-wire seemed endless. Every ten steps, a sigh: To the Baths and Inhalations. Then the herd passed by a row of anti-tank spikes, then along an anti-tank trench, then by a hedge of coiled thin steel wire; finally, down a long, open-air corridor between yards and yards of barbed-wire. Ernie was carrying a little boy who had fainted. Many were supporting one another. And in the crowd’s more and more crushing silence, in its more and more pestilential stench, smooth and graceful words sprang to his lips, scanning the children’s steps with reverie, and Golda’s with love. It seemed to him that an eternal silence was closing down upon the Jewish cattle as it was led to the slaughter; that no heir, no memory would supervene to prolong the silent parade of victims; no faithful dog would shudder, no bell would toll; only the stars would remain, gliding through a cold sky. ‘O God,’ the Just Man Ernie Levy said to himself, as the blood of pity streamed from his eyes, ‘O Lord, we went forth like this thousands of years ago. We walked across arid deserts, through the Red Sea of blood, in a deluge of salt and bitter tears. We are very old. We are still walking. Oh, we would like to arrive at last!’

The building resembled a huge bath-house; to the left and right, large concrete pots cupped the stems of faded flowers. At the foot of the small wooden stairway an S.S. man, mustachioed and benevolent, told the condemned, ‘Nothing painful will happen? You just have to breathe very deeply. It strengthens the lungs. It’s a way of preventing contagious diseases. If disinfects.’ Most of them went on in silence, pressed forward by those behind. Inside, numbered coat-hooks garnished the walls of a kind of gigantic cloakroom where the herd undressed one way or another, encouraged by their S.S. cicerones, who advised them to remember the number carefully; cakes of stony soap were distributed. Golda begged Ernie not to look at her, and he went through the sliding door of the second room with his eyes closed, led by a young woman, and by the children, whose soft hands clung to his naked thighs; there, under the shower-heads embedded in the ceiling, in the blue light of screened bulbs glowing in recesses of the concrete walls, Jewish men and women, children and patriarchs, were huddled together; his eyes still closed, he felt the pressure of the last packets of flesh that the S.S. men were clubbing now into the gas chamber; and his eyes still closed, he knew that the lights had been extinguished on the living, on the hundreds of Jewish women suddenly shrieking in terror, on the old men whose prayers rose immediately, growing in strength, on the martyred children who were recovering in their last agonies the fresh innocence of older anguishes, in a chorus of identical exclamations: Mummy! But I was a good boy! It’s dark! It’s dark! … and when the first waves of ‘Cyclon B’ gas billowed among the sweating bodies, drifting down towards the squirming carpet of children’s heads, Ernie freed himself from the girl’s mute embrace and leaned out into the darkness towards the children invisible even at his knees, and shouted, with all the gentleness and all the strength of his soul, ‘Breathe deeply, my lambs, and quickly!’

When the layers of gas had covered everything, there was silence in the dark sky of the room for perhaps a minute, broken only by shrill, racking coughs and the gasps of those too far gone in their agonies to offer a devotion. And first as a stream, then a cascade, then an irrepressible, majestic torrent, the poem which, through the smoke of fires and above the funeral pyres of history, the Jews — who for two thousand years never bore arms and never had either missionary empires or coloured slaves — the old love poem which the Jews traced in letters of blood on the earth’s hard crust unfurled in the gas chamber, surrounded it, dominated its dark, abysmal sneer: ‘SHEMA ISRAEL, ADONAI ELONHENU ADONAI EH’OTH. . . Hear O Israel, the Eternal our God, the Eternal is One. O Lord, by your grace you nourish the living and by your great pity you resurrect the dead; and you uphold the weak, cure the sick, break the chains of slaves; and faithfully you keep your promises to those who sleep in the dust. Who is like unto you, O merciful Father, and who could be like unto you? . . . ‘

The voices died one by one along the unfinished poem; the dying children had already dug their nails into Ernie’s thighs, and Golda’s embrace was already weaker, her kisses were blurred, when suddenly she clung fiercely to her beloved’s neck and whispered hoarsely: ‘Then I’ll never see you again? Never again?’

Ernie managed to spit up the needle of fire jabbing at his throat and, as the girl’s body slumped against him, its eyes wide in the opaque night, he shouted against her unconscious ear, ‘In a little while, I swear it!. . . ‘ And then he knew that he could do nothing more for anyone in the world, and in the flash that preceded his own annihilation he remembered, happily, the legend of Rabbi Canina ben Teradion, as Mordecai had joyfully recited it: when the gentle rabbi, wrapped in the scrolls of the Torah, was flung upon the pyre by the Romans for having taught the Law, and when they lit the faggots, branches still green to make his torture last, his pupils said, Master, what do you see? And Rabbi Chanina answered, I see the parchment burning, but the letters are taking wing . . . ah, yes, surely the letters are taking wing, Ernie repeated as the flame blazing in his chest suddenly invaded his brain. With dying arms, he embraced Golda’s body in an already unconscious gesture of loving protection, and they were found this position half-an-hour later by the team of Sonderkommando responsible for burning the Jews in the crematory ovens. And so it was for millions, who from Luftmensch because luft. I shall not translate. So this story will not finish with some tomb to be visited in pious memory. For the smoke that rises from crematoria obeys physical laws like any other: the particles come together and disperse according to the wind, which propels them. The only pilgrimage, dear reader, would be to look sadly at a stormy sky now and then.

And praised by Auschwitz. So be it. Maidanek. The Eternal. Treblinka. And praised be Buchenwald. So be it. Mauthausen. The Eternal. Belzec. And praised be Sobibor. So be it. Chelmno. The Eternal. Ponary. And praised be Theresienstadt. So be it, Warsaw. The Eternal. Wilno. And praised be Skarzysko. So be it. Bergen-Belsen. The Eternal. Janow. And praised be Dora. So be it. Neuengamme. The Eternal. Pustkow. And praised be. . .

At times, it is true, one’s heart could break in sorrow. But often, too, preferably in the evening, I cannot help thinking that Ernie Levy, dead six million times, is still alive, somewhere, I don’t know where . . . Yesterday, as I stood in the street trembling in despair, rooted to the spot, a drop of pity fell form above upon my fact; but there was no breeze in the air, no cloud in the sky . . . there was only a presence.

*******

And here I am, sobbing again, as I was upon first reading.

Some years ago, I asked a friend, a Catholic nun, what I should do when they come for my neighbors. “Go with them,” she said.

How long will it take to learn the names of the “disappeared,” and the dead?

When does ‘never again’ mean never again for anyone?

It feels like too many people are disappearing into enteratinment and sitraction, watching shows like The Last of Us rather than confront reality and reading a book like The Last of the Just.

Thanks for the recommendation (and for this series of posts, more generally); I’ve added it to my list. I recently reread Maus (after about 30 years); I hadn’t remembered that basically the entire first volume is dedicated to the slow progression of fascism for the family members in decades prior (and the second to the camps), an essential reminder that these atrocities do not “come out of nowhere”.

Hi Marcie! I hear you (and appreciate the clever turn of phrase). On the other hand, I watched a Gerrard Butler film the other day for sheer escapism. It was SO tense all the way, that I simply couldn’t register any other fears! Not at all sorry. lol

Maus is brilliant, and of course, now banned in many places. I’m also reading Timothy Snyder’s “On Freedom,” which feels essential. I understand Snyder has left Columbia and will be taking up a post at the U of T. I can understand why.

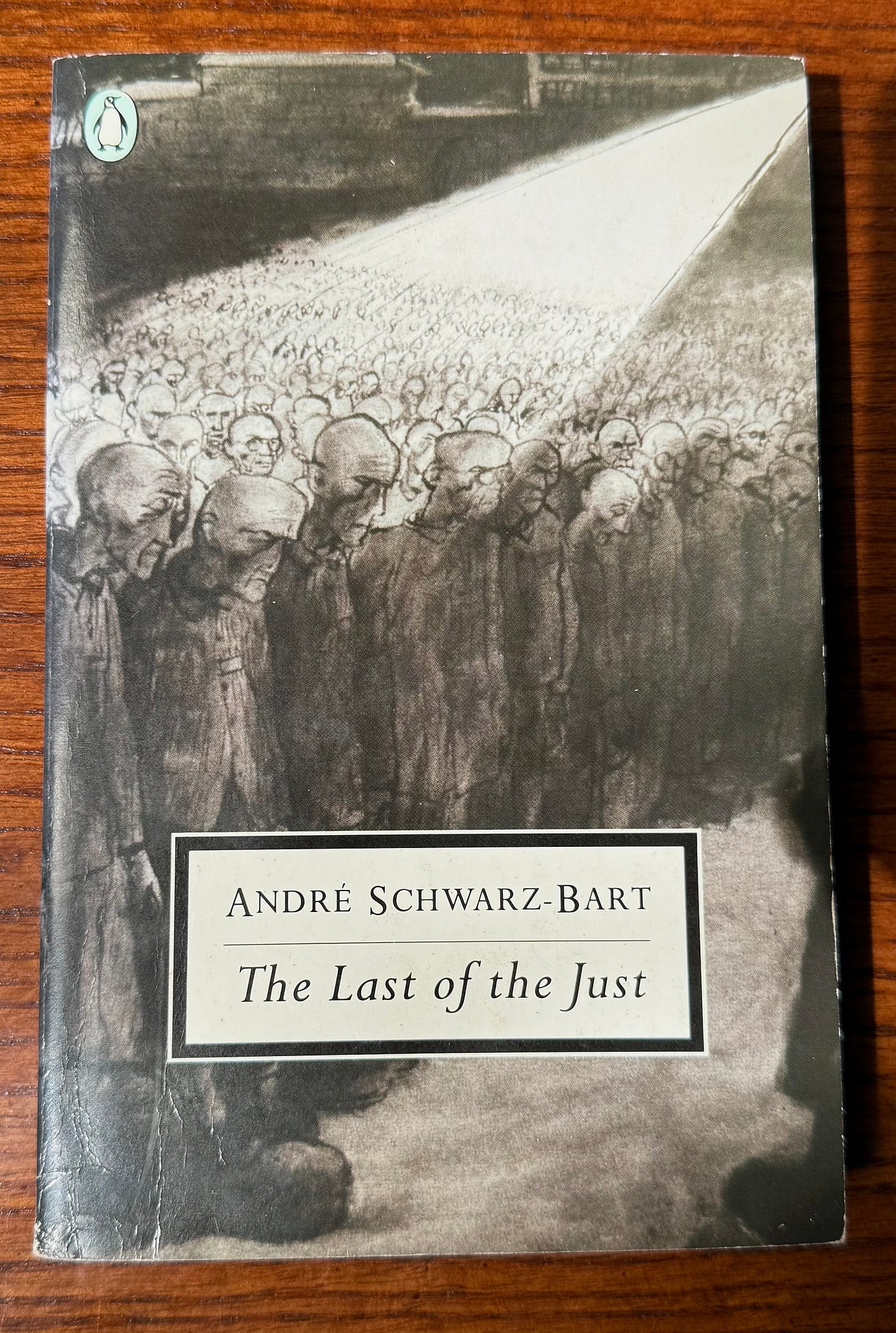

HI Lauren, I love this book and I’ve never seen this edition before! Could you please tell me the ISBN number and/or provide more pictures of it? Would be much appreciated as I want to find it

Hi Nathan, according to the bookstore Barnes and Noble, the ISBN-13 is 9781585670161 and the

Publisher is The Overlook Press. I have an older version but this is the book. If you’re in Australia, and I think you are from your email, I’m sure any good bookstore would order it for you.

Hi Lauren, thanks for your reply! I would like to find the older version that you have which looks like a Penguin 20th Century Classic. Could you tell me the ISBN number for that edition as listed in that book?

(I love this book – I wrote about it in my own book on refugees)

Hi Nathan, I have the Penguin US edition from perhaps 1986 or 7. I don’t have it in front of me, but when I’m back home on Friday I’m happy to look it up and post it here. This book means a great deal to me. So I’m sorry but I just can’t sell it. Perhaps if you send the photo of the cover to a second hand book dealer they may be able to help.

thank you that is helpful. I will try to find it – I suspect it is hiding behind a stock photo image 😉

My book is called refugees: towards a politics of responsibility. The first and last words belong to Schwarz-Bart, by design.

yes and please do post details/images when you can, much appreciated!

Also, what’s the name of the book you wrote?

I look forward to reading your book. Thanks. And I’ll post the details when I get home. 😁

Hi Lauren, did you manage to find it? Cheers