Monsters and Artists

I recently read a Weekly Standard review of The World Is What It Is: the authorized biography of V.S. Naipaul, written by Patrick French. In this biography, an authorized one I remind you, Naipaul talks about beating women, being a sexual sadist and a racist. The review begins this way:

During a brief remission in his wife’s cancer, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist V.S. Naipaul casually explained to a journalist that he had always been “a great prostitute man,” mongering among the whores from the early days of his marriage.

The publicity that followed from the remark “consumed” his wife, he later admitted to his biographer, Patrick French. “She had all the relapses and everything after that. She suffered. It could be said that I killed her. . . . I feel a little bit that way.” Unfortunately, he didn’t feel “that way” enough to think it inappropriate to move into his house, the day after he cremated his wife, his new mistress, a Pakistani journalist he’d just met (and would, in short order, marry).

Even before the whoring revelations, Naipaul’s first wife, a middle-class woman named Patricia Hale whom he’d met while he was a student on scholarship to England, had known about a prior mistress–but only because Naipaul himself decided one day to tell her, explaining the violent acts he enjoyed with the woman, some of them memorialized in photographs he brought along to aid the explanation.

The woman’s name was Margaret Gooding, and Naipaul met her in 1972 in Buenos Aires. French’s new biography of Naipaul, The World Is What It Is, quotes extensively from her letters: unbearable scrawls that read like clinical case studies drawn from the pages of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. She begs, moans, despairs, and pleads for Naipaul’s “cruel sexual desires.” She calls him her “god,” her “black master.” Her multiple abortions of his children sicken her, but she offers them up to him as proof of her love and abasement.

And all this sex stuff is only the beginning. Throughout The World Is What It Is Naipaul shows himself arrogant beyond belief, and vile-tempered, and as self-obsessed as a man simpering while he looks at himself in the mirror. His letters and conversation are full of references to “niggers” and dismissals of Africans and dark-skinned Indians.

The man was capable of bouts of extraordinary cruelty: Unhappy with Margaret at one point, Naipaul explains, “I was very violent with her for two days. . . . Her face was bad. She couldn’t appear really in public. My hand was swollen.” But then, he was capable of ordinary, everyday cruelty, as well: “You are the only woman I know who has no skill,” his wife’s diaries reveal Naipaul once told her, just in passing. “You behave like the wife of a clerk who has risen above her station.” He moved on to the mistress who would become his second wife because his inamorata Margaret had simply grown unworthy of his use: “middle-aged, almost an old lady.”

Sir Vidia S. Naipaul. Sounds like a pleasant chap, doesn’t he?

Maybe these revelations, horrifying as they are, shouldn’t come as such a shock. In Naipaul’s book, “A Bend in the River,” perhaps he told us precisely what his world view was when he began with the line: “The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.” Up until now, I had assumed this was merely a literary construct, the premise on which the book’s exploration was based, and by no means the actual world-view of the author. Now, I’m not at all sure.

For me, particularly in light of this new biography, this sentence raises several questions: 1) what does Naipaul mean by the world being what it is, and if, as is inferred, he means the world is competitive and harsh and ruthless, then 2) is Naipaul’s second assumption correct? Do those who allow themselves to become nothing — by which I assume Naipaul mean’s not famous, not powerful, not ‘important’ – have no place in the world? 3) is becoming ‘something’ the unqualified goal of life, or should there be certain qualifiers attached, say, like goodness, or kindness, or justice? and 4) if an artist is an ass and a thug and a criminal, can I appreciate his work in spite of knowing this?

(I will leave the question of why someone would want to reveal all this pus and decay to the psychiatrists, although Joseph Bottum, who wrote the review, concludes it is a back-handed attempt to outrun the post-death slump that writers face, a slump which must be overcome to ensure a writer’s place in the lasting canon.)

I’ll go on the record here. I think there are several problems with Naipaul’s statement concerning human ‘nothings’. For one, I don’t think Naipaul is qualified to tell me what the world is. He, like any writer (or anyone else for that matter) is only qualified to tell me what his world is like. Alas, Naipaul comes across as so arrogant that he would, I suspect, scoff at such a distinction. Well, sorry, but although Sir Vidia is undoubtedly quite bright, he isn’t omniscient, and therefore I can’t accept that he’s figured out what, precisely, the world is, when other great minds, you know, those philosophers and physicists and theologians and molecular biologists and so forth, haven’t been able to. This may be his experience of the world, and perhaps this supports the adage that one should be careful what one thinks, since the world IS that way.

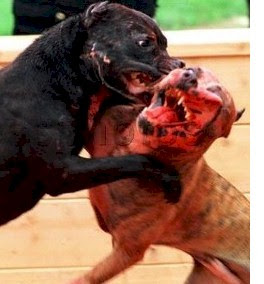

It must hurt like hell to live in a dog-eat-dog, suvival-of-the-fittest world.

How painful it must be to live in a world so unforgiving, so hostile. My own experience of the world is quite different. I see it tilted toward creation, endlessly merciful, even in agony (of which I have some small experience), beautiful beyond measure, even in want and squalor (of which I also have some small experience), and where it is harsh and vi

olent and red-of-tooth-and-claw, still my experience has been that love yet abides, and that I am not cast aside, I am not alone, I am companioned.

Further, I don’t believe anyone is a nothing, ever. I’m one of those whackos who actually believe in a Power Greater Than Myself, and I don’t believe that Power, overlooks anyone, or dismisses them because they haven’t earned the approval of people like V.S. Naipaul. I find we have little perspective on our own lives, we don’t know who we have touched or whose paths we have eased. In short, we don’t know how that tilted-toward-creation-and-compassion universe has made use of us. Even “The Least” among us.

I am not afraid of being ‘nothing’ as Naipaul puts it. If I’m afraid of anything, it is in failing to be useful to what I believe is the goal of the Ineffable. I can, and have, been many somethings — a drunk, a liar, a thief, a gossip, a bad friend, a bad employee. Lots to be ashamed of, and many things for which I needed to make amends. You can’t call the tornado of pain that an active alcoholic is to anyone who crosses her path a ‘nothing,’ can you? No, it’s certainly a something. But is that what one aspires to? I hope not. I aspire to be many things – useful, compassionate, kind, just, honest, creative, trustworthy, etc. I aspire to live out the will of the Ineffable, which may best be summed up in the prayer known as The Saint Frances Prayer. Of course, most days I fail miserably, but because the world I live in is compassionate and full of grace, I get another chance tomorrow.

St. Francis of Assisi – who craved nothing, that he might find everything

Which brings me to my final question — if the master artist is an unrepentant (and that’s the key word here) ass, thug and criminal, can I appreciate the art, while not supporting the artist? Or should I bother to have an opinion on it at all? Should I simply accept great art for itself and leave the judging to.. well, someone better qualified, like The Great Unknowable.

And so we’re back to the unrepentant thing. I wrote in an earlier post about the difference between forgiveness and reconciliation. This speaks to that. If, as seems obvious by Sir Vidia’s apparent delight in his vile and hurtful actions, he feels no remorse, no sense of repentance, it is quite impossible for me to reconcile myself to the man. But if I don’t know anything of the man, can I still appreciate the beauty, the precision, the clarity of his writing. Sure I can. Sadly, Naipaul has deliberated opened his raincoat and waggled his dangling bits in my face.

It’s like Miles Davis — self-acknowledged pimp, batterer of women, and jazz genius. I LOVE Miles Davis’s music. I find it transcendent and glorious — proof that sacred beauty turns up in all sorts of unlikely places. However, I never bought a single one of Miles Davis’s albums until after he died. That’s just personal choice, of course, but I felt I couldn’t support the man’s unrepentant cruelty. The day he died, though, I ran out and bought everything he’d ever done. I figured his survivors could use the cash.

Writers and other artists are not, of course, required to be great human beings. If we look at the lives of any number of great artists, well, we may be sorry we asked. Still, this sort of soul-sickness is hard to witness, and I, for one, feel the need for distance. Sadly, I’ll never be able to read his work the same way. And wouldn’t it be ironic if his own desperate-seeming self-revelation becomes the rock through the bottom of the lifeboat, sending his reputation, and his work close behind it, to the depths of a forgetful sea?

Copyright 2008 Lauren B. Davis For permissions: laurenbdavis.iCopyright.com