Into the dark midwinter (with glimmers)

And the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night, my dear.

— Thomas Moore

Unlike a writer I know, Louise, who lives inconveniently in Alaska, where she suffers terribly from depression during the dark winters months, I adore the short days and long nights of this season. My complaint is that summer is too long, and winter too short down here in New Jersey. I am, I’m afraid, rather melancholy by disposition, and thus this season suits me. During the pre-solstice season I am at last in sync with my environment, as it were. Quiet and reflective, contemplative, cocooned. I suspect I was, in a previous life, some sort of hibernating, long-dreaming creature. A hazel dormouse, perhaps, a creature which hibernates from October to April in a tightly curled position in order that it might conserve heat. That’s me, hot water bottle pressed up against my belly.

At this time of year I can get up before the sun (without having to get up at 4:00 a.m.), and watch the thin milky light of winter slowly bring the world back into soft focus on these drizzly days. I can be productive for a reasonable period of time, writing for say, six hours a day, and then I can retreat to a comfy spot in front of the fire with a book in hand while the world approves my choice by politely tucking itself up in the velvet cloth of evening. And although I do long for the snow-reflected bright light of my childhood memories in Canada, I am equally happy with fog and mist lurking around black-limbed trees against an argent sky. I long for snow, I must admit, and that special sort of muffled world that exists only under the blanket of deep snow, but then we’re always longing for something, aren’t we?

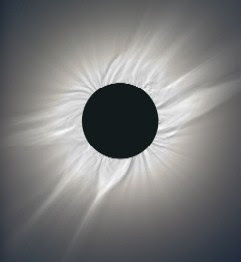

The great gift of this season is that we know the light will return. Even I wouldn’t want to live my entire life in a world of perpetual gloom, with the sun barely peeking over a distant horizon before disappearing again and without the consolation and inspiration of northern lights. No, the reason I am nourished by this season, is that I know it is part of the natural order of things, that this going within and trusting the dark has something to teach me, something that I will be able to make use of when the seasons shift, and I am asked to go out into the world again and be useful in a different, more active way.

It’s no wonder that so many religions — in fact, I suspect all of them in one way or another — have found a way to mark this darkness-into-light-reborn period as their own. It permits us to fully experience the dark, while in faith we understand that this too shall pass. If felt deeply, and lived fully, it can also become a deeply embedded experience to draw on when we find ourselves in dark times of other sorts.

As someone who has struggled with addiction and, one day at a time, made it through nearly fourteen years of sobriety, I often hear people speak about “having to hit bottom” before addicts are truly willing to do whatever it takes to get sober. This is another way of saying they have to go fully into the darkness before they can find the light again. As addicts, we are crippled by faulty perceptions. We do not see the world as it is, or rather, we see the world only through the lens of our disease. In short, our disease tells us the light will never return, if it ever existed at all. I think this is why addiction is often referred to as a spiritual disease — because active addicts forget that the darkness is temporary, that light will return. We lose our faith. We become lost in the dark, panicked, selfish in our survival-terror, insistent there is no other way. We stay like that until we exhaust ourselves, until we run headlong, in our blindness, into a brick wall and then, if we’re lucky, someone comes along with a lamp and leads us, willing at last, back towards the incrementally lengthening day and the miracle of transformation.

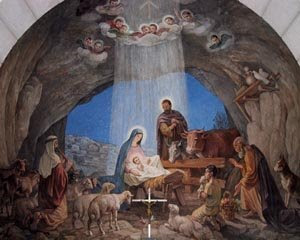

So. Here we are. In the mid-winter, and solstice soon to come, a time of darkness which leads, or can lead, to great transformation. I, for one, am inspired by the fact that this is a sacred time for peoples all around the world, and has been such since long before someone decided to use the date as that of Christ’s birth. And speaking of that – the earliest mention of December 25 as Jesus’ birthday dates to 354 ce. (To be truthful, we don’t even know the year Christ was born in — modern scholars think it could have been anytime between 4 and 1 bce.)

(Okay, to be REALLY truthful, we don’t even really know where he was born for sure. Mark and John say Nazareth was his hometown, as does Jesus himself, Luke and Mathew both set the story of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem.) (For a particularly witty examination of this sort of thing, I recommend Don’t Know Much About the Bible, by Kenneth C. Davis) In ancient time, December 25 was, give or take a day, the date of the winter solstice. In Rome, the week before the solstice was the Saturnalia, a sort of orgy that ended with gift-giving and candle-lightning.

There is evidence of pre-Christian Germanic peoples using wreathes with lit candles during the cold and dark December days as a sign of hope in the future warm and extended-sunlight days of spring. In Scandinavia, people lit candles and placed them around a wheel, a symbol known as the “sun wheel” and they offered prayers to the god of light to turn “the wheel of the earth” back toward the sun to lengthen the days and restore warmth. By the Middle Ages, the Christians adapted this tradition and used Advent wreathes as part of their spiritual preparation for Christmas, a symbol of their belief that Jesus Christ is “the Light that came into the world” to dispel the darkness of sin and to radiate the truth and love of God (cf. John 3:19-21).

Native Americans had winter solstice rites as well. There are, for example, sun images on rock paintings of the Chumash, who occupied coastal California for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. Solstices were tremendously important to them, and the winter solstice celebration lasted several days.

Among the Iroquois, the winter solstice was the dreaming time, and still is for traditional people. This was the time of year when, rather than partying all night, you turned in early, you dreamed… The People of the Longhouse used the solstice as a time to walk between the worlds of light and dark. This was the time when Grandmother Moon and Mother Night were most powerful, and would bring dreams from The Great Mystery which were full of meaning. At first light, all the people gathered, and shared the vision they had received on this most sacred night.

The dreams would be discussed at length, and the meaning deciphered, for it was understood that these dreams held information not merely for the individual, but for all the people, and for all the world. The Iroquois, the Haudenoshonee, as they call themselves, practiced this annual event for 1,000 years before the first European set foot on these shores. French Jesuit missionaries in the 1600s marveled at the Iroquois’ annual event, writing about them in letters and journals, especially the aspect of the tribe “acting out” various dreams.

In Judaism, the placement of Hanukkah is tied to both the lunar and solar calendars. It begins on the 25th of Kislev, three days before the new moon closest to the Winter Solstice. In 2008 it will begin on December 21st, which is also the time of this year’s solstice (although Hanukkah is not specifically tied to the solstice, and can fall as early as the end of November). Nearly 2,200 years ago, the Greek-Syrian ruler Antiochus IV tried to force Greek culture upon peoples in his territory. Jews in Judea – now Israel – were forbidden their most important religious practices as well as study of theTorah. Although vastly outnumbered, religious Jews in the region took up arms to protect their community and their religion. Led by Mattathias the Hasmonean, and later his son Judah the Maccabee, the rebel armies became known as the Maccabees. After three years of fighting, in the year 3597, or about 165 B.C.E., the Maccabees victoriously reclaimed the temple on Jerusalem’s Mount Moriah. Next they prepared the temple for re-dedication — in Hebrew, Hanukkah means “dedication.” In the temple they found only enough purified oil to kindle the temple light for a single day. But miraculously, the light continued to burn for eight days.

Ah yes, the miracle of light again, and the re-dedication, which might also be called transformation.

There’s a rather good article on Wikipedia about all the various festivals past and present that happen around this time of the year, and it makes a fascinating read.

My own recent research (for a new novel I’m working on) into 7th c. Anglo-Saxon practises tells me that Yule had a great significance for the Germanic/Scandinavian peoples of the period. Obsessed as they were with fate and absolutes, as Christopher Dewdney says in his lovely book, Acquainted with the Night, they heralded this time as both an end and a beginning, the end of the journey into darkness and the beginning of the dawn of hope. According to Norse legends, Odin rode his magic, eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, on this night and it was traditional for Norse children to leave offerings of hay and sugar for Sleipnir in their boots and shoes, placing them by the hearth on solstice eve. They hoped Odin would leave them a gift in return for feeding his horse. In the tradition of candles and Christmas lights, it’s easy to see the memory of Yule logs the fires built by ancient peoples as a way to call back the power of the sun.

Winter solstice has been overlaid with Christmas, at least in the western world, for some time now. (Don’t get me started on consumerism and commercialism!) But I wonder — and I’ll bet you have as well — if we haven’t diluted the deep connection we once had with the sacredness of the earth, the cosmos and the seasons both of earth and of our lives. So perhaps, if you are like me, you can give yourself permission to deeply experience this time of darkness-with-the-promise-of-light, and if you are like my friend Louise, perhaps, understanding that an encounter with darkness is sometimes the very path which leads to light, it will be less difficult.

In the midst of all the holiday preparations and madness, can we not take a moment to ponder the mystery contained in the darkness, and the transformation of the coming light? Can we not permit ourselves to have a transforming encounter there, right there, at the darkes

t moment, when all becomes light again?

I wish you transcendent, meaningful dreams…

Copyright 2008 Lauren B. Davis For permissions: laurenbdavis.iCopyright.com