Galaxies, holographs, physicists and theologians

A number of years ago, my Best Beloved and I were invited to Magdelan College, Oxford, to have dinner at the high table. It was quite an honor, bestowed upon us through no merit of our own, but because my Best Beloved’s cousin was a don there.

We met in one of the many ivy-covered buildings for sherry first (well, diet cola for me) and it was suggested if I needed the ladies’ room that I should use it now, for there were no facilities for women inside. Harrumph. Never mind. The Best Beloved’s cousin led us upstairs to an airy room painted a rather industrial shade of yellow and were greeted by a large number of men (no women, as I recall) all wearing their long black robes, and swilling the aforementioned sherry. One man, an anthropologist of some sort, who smelled of cigarettes, insisted on lecturing me into a near coma on Native Canadian politics, with little apparent first-hand knowledge of the subject. Ah well.

Just when I thought I might have to chew my leg off to extricate myself from this conversational trap, someone announced we were ready to head to the high table and, with that, a casement window flew open and several of the old dons stepped out into the night sky. I wondered for a moment if I were witnessing a mass suicide, but was quickly reassured that there was a short cut across the roof into the main dining hall. When my turn came I was relieved to see that some forward thinking engineer had built a metal catwalk with nice high railings in order that these adventurous academics and their guests didn’t tumble off the slate to the cobbles below.

Once in the dining hall we were shown to our seats at the high table and someone next to me muttered rather uncharitably about being seated near the physicists. PHYSICISTS?? Really? Oh, nothing could have been more wonderful to me! It’s all well and good to sit with a bunch of writers all night yakking about how awful this or that critic has been, or griping about who did or didn’t get grants this year, but it’s nothing compared to the conversational joys available with great scientists.

I leapt, conversationally speaking, upon the wild-haired, bespectacled, somewhat undernourished-looking physicist with great enthusiasm, which initially seemed to scare him a little, perhaps the result of long years of being given the cold shoulder by less-than admiring anthropologists. He recovered quickly, thought and in no time was explaining the possibilities of a holographic universe to me, or at least trying gallantly to do so. I freely admit it was often beyond my ken. He talked about how Allain Aspect and his team discovered that under certain circumstances subatomic particles such as electrons are able to instantaneously communicate with each other regardless of the distance separating them. It doesn’t matter whether they are 10 feet or 10 billion miles apart. And went on to discuss how the University of London physicist David Bohm believe Aspect’s findings imply that objective reality does not exist, that despite its apparent solidity the universe is at heart a phantasm, a gigantic and splendidly detailed hologram.

REALLY??? How, how fantastic!

It was a grand evening, and although I only understood perhaps a third of what my new friend had to say, I remember my head filling with universes within universes, time curving around on itself and and tiny particles flying about faster than the speed of light, which is enough, I think, to give anyone mind cramps. Bliss.

Now, I’m not a physicist-snob. I am just as happy talking to geologists, biologists, botanists, astronomers or even chemists, for that matter. These are the folks who get to poke around inside the inner workings of the universe, who are face to face with the great mysteries, every single day!! What fun! Talk to me of quarks and leptons, whisper in my ear of nebulas and DNA helixes, murmer to me of rock strata, ammonites, and glacier movements, quote me the poetry of black holes and sing me the canticles of spiral galaxies, thrill me with sweet-talk of bio-luminesence!

Darkness in Antarctica’s Weddell Sea gives this comb jelly a chance to show off its candy-colored bioluminescent cells.

I have as much fun talking to scientists as I do to theologians, and for the same reason — because all these people are interested in how the universe works, what makes it tick. Loren Eiseley, the great scientist-poet, said this:

“Ever since man first painted animals in the dark of caves he has been responding to the holy, to the numinous, to the mystery of being and becoming, to what Goethe very aptly called ‘the weird portentous.’ Something inexpressible was felt to lie behind nature.”

I’m not saying all scientists feel that sense of mystery, but I know that when I talk with them, or when I gaze up into the night sky, or into a tidal pool, upon the gnarled roots of a tree, the undulating gorget on a hummingbird’s throat or into the glittering heart of an amethyst geode, I am filled with a sense of something so wondrous, so much greater than I am, that I can’t help but respond with gratitude and awe. That’s holy, to me.

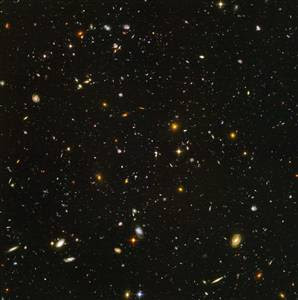

Some dark nights, I look up and, if I’m lucky enough to be in an area not overwhelmed by light pollution (don’t get me started!) I notice a band of light stretching across the sky — the Milky Way, our barred spiral galaxy — a gigantic collection of stars, gas and dust in which our solar system is located. It’s an enormous galaxy, containing an estimated 200 to 400 billion stars, and as if that weren’t enough to keep you in wonder for the rest of your days, beyond that are billions of other galaxies — some similar to our own and some wildly different — scattered throughout space to the very limits of the observable universe.

Think of that — billions — and if we’re using the short scale as in America, that’s 1000 milli

on, or 1,000,000,000, but, if we’re using the long scale, as in Europe, that’s a million million, or 1,000,000,000,000! Now, you might say that with such a huge difference between a thousand million or a million million, how can I be so cavalier? Well, honestly, my mind can’t really get around either of those figures, they’re so big. Imagine — spiral galaxies, elliptical galazies, irregular galaxies. The closest one to us is the recently discovered Canis Major dwarf galaxy, an irregular galaxy now thought to be our closest galactic neighbor, just over 25,000 light-years away. Close as the corner store, galactically-speaking.

It’s very hard to believe in a me-centered creation, or even a human-centered creation in the face of such vastness, but not at all difficult to believe in what my Ojibway friends call “The Great Mystery.”

I have a young, scientifically-minded friend who recently asked me how I can possibly believe in God, since it’s all such obvious nonsense. He can’t understand how someone like me, with no other obvious evidence of mental infirmity, someone who loves to read science writers and ponder biostratigraphy, dark matter and triblobites can possibly believe in such childish fairy-tales.

Well, what can I say? I do believe in God, if you will accept my calling God, The Ineffable. Or, rather it’s probably truer to say I hope in God, since belief seems to imply a kind of certainty, and I am rarely certain about anything, and less so the older I get.

Why do I hope in God? For a number of reasons, but for today I’ll mention only a couple:

First, because I can’t see any downside, since The Ineffable of my understanding has no preference for Jews or Muslims or Christians or Hindus, and thus spurs me only to compassion and understanding and not superiority or exclusivity.

Second, because cultivating a sense of gratitude and wonder in this universe I call home means I stay right-sized, not taking myself too seriously. That’s why I love starting my day with, for example, the Astonomy Picture of the Day — it’s such a great reminder that in a universe of such great creative capacity, such profound diversity and complexity, my own wee problems amount to very little, really, and my mental health is much improved by focusing not on whatever’s irritating me at the moment, but in a contemplation of The Grandeur, if you will of The Great Mystery.

Sometimes, when I close my eyes and sit still for a while, I find I can almost imagine that there is no frontier between myself — all my own atoms and molecules and helixes — and the impossibly vast reaches of beyond, that the space between the cells of my body are the spaces between planets and all that is without and all that is within are the same, immeasurable, limitless, at once completely empty and completely filled. The experience is one of utter peace, overlaid with boundless creative energy…. is that a mystical experience, a numinous experience, or just a good imagination? I don’t know, so I’ll call it prayer.

Doesn’t happen often, of course, but oh, when it does! It’s more addictive than any wine, any drug, and it’s what keeps me going back to the physicists, the scientists, and yes, those marvellous theologians and philosophers like Duns Scotus, who taught immanence rather than transcendence, that the material world was a sacramental symbol of God, not something separate from him and/or her.

Copyright 2008 Lauren B. Davis For permissions: laurenbdavis.iCopyright.com