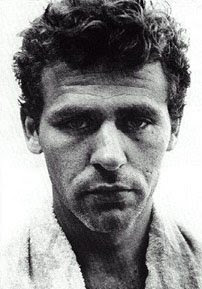

Original inspiration – James Agee

I was, I think, fourteen, perhaps fifteen when someone I can’t recall handed me a book, called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The ‘someone’ was a woman, older than I, and I vaguely recall we were sitting in a kitchen, drinking tea. I have an image of wooden floors, a pot-bellied stove, sagging bookshelves, and a red and white checkered plastic table cloth. I can’t for the life of me imagine where this might have been, or who this woman might have been and I suspect I am superimposing the scenes and settings of the book onto the moment when I discovered it. Nonetheless, it was a moment that changed my life.

Up until then I had hoped to be a writer. Well, perhaps not even hoped. Fantasized is probably more accurate a word. I scribbled. Wrote lyrics to songs I sung while accompanying myself, poorly, on the guitar. I kept a journal in which I noted the deepest, most compelling and insights into my soul – all adolescent self-centered blather, of course. I wrote appalling poetry. But in the artsy circle of my friends, none of these activities was particularly noteworthy – we were all scribblers and singers and poets, anguished, tormented, horribly sincere, which is to say, we were all teenagers. I had no real idea that I might actually find a life’s work in this activity.

And then I read Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the book that resulted from an article he and photographer Walker Evans were assigned (for Fortune, I believe) on the horrific living conditions of white Alabama sharecroppers during the Great Depression. (One can only imagine what it must have been like for their black counterparts.) I was stunned. The language, yes. The mad rushing mix of poetry, the biblical cadence of the prose; the raw, harrowing subject matter.. all of that, but something more: Agee was desperate to make the reader understand. Desperate. In particular, pages 75-82. On these pages Agee describes the Gudgers and the world they live in, and part way through the passage I began to feel that Agee was afraid he was going to fail, to fail us, the reader, but more importantly, to fail the people about whom he wrote. I understood that, having lived with these people and learned to care for them, not as statistics of the Great Depression but as men and women of supreme value, unique, peerless and beloved of God, Agee was writing as though his very soul depended on bearing proper witness.

The prose in this passage begins quietly, elegiacally, and slowly builds, moving psychically closer and closer in, from the land and the town to the minds, dreams, hopes of the people sleeping in the shack wherein Agee writes. The sentences become shorter, the phrasing blunter, the structure less organized, as Agee becomes more and more frantic…until he breaks into a series of punctuation marks:

(But I am young; and I am young, and strong, and in good health; and I am young and pretty to look at; and I am too young to worry; and so am I, for my mother is kind to me; and we run in the bright air like animals, and our bare feet like plants in the wholesome earth; the natural world is around us like a lake and a wide smile and we are growing: one by one we are becoming stronger, and one by one in the terrible emptiness and the leisure we shall burn and tremble and shake with lust, and one by one we shall loosen ourselves from this place, and shall be married, and it will be different from what we see, for we will be happy and love each other, and keep the house clean, and a good garden, and buy a cultivator, and use a high grade of fertilizer, and we will know how to do things right; it will be very different:) (?:)

How did we get caught?

(? ))% ( (?) ) #*(

Before the era of text-speak, these symbols were, to me, an indication of frustration, desperation, and Agee’s rage against his own perceived inadequacy.

He goes on:

How were we caught?

What, what it is has happened? What is it has been happening that we are living the way we are?

The children are not the way it seemed they might be:

She is no longer beautiful:

He no longer cares for me, he just takes me when he wants me:

There’s so much work it seems like you never see the end of it:

I’m so hot when I get through cooking a meal it’s more than I can do to sit down to it and eat it:

How is it we were caught?

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain; and when he was set, his disciples came until him:

And he opened his mouth and taught them, saying:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for there’s is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

….

And so on, to the end of the beatitudes. To this day, to the moment of this writing, I cannot read that passage, p. 75-82, without weeping.

To this day, to the moment of this writing, reading that passage confirms that the only thing I want to do with my life is to write.

What did reading Agee do to me? What does it do to me? For one, it drags me into a world I will never otherwise know and rips open my eyes and my heart so that I might see it afresh, saturated with empathy. I cannot live as a sharecropper in the 1930s, but, through Agee’s writing, I experience another person’s reality. Because the work is so well written, I FEEL what these people are feeling, taste their food, smell the stale sheets, feel the cold, hear the barking dogs, experience the hope and despair. In short, I am made more human, more compassionate, more empathetic, through my experience of their lives.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is not a perfect book. Far from it. It is flawed, messy, meandering, and now when I read it over I swear I can pick out the moments when Agee’s drinking (which finally killed him prematurely at the age 56 of 1955) gets the better of him and the prose slips into maudlin incoherency. It doesn’t matter. In a recent article in the Harvard Magazine, Adam Kirsch says, “Suddenly, he [Agee] was no longer writing a magazine article about a socio-economic problem; he was undergoing something very like a spiritual ordeal, in which he was granted a vision of the infinite value of each individual human being, even or especially the poorest.” And he goes on to say, “In Agee’s hands they [the five W’s of journalism] have been transformed into a metaphysical mystery.”

Agee’s own story is one of restlessness, irritability, and discontent, and many people have speculated on why such a spectacularly gifted writer ultimately produced so little work. Apart from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee is remembered for the posthumously published novel A Death in the Family, and some of the best film reviews ever written. However, one has to wonder how much else he might have written, had he lived, and well…. sobered up. Bad work habits have been blamed, long soul-sucking stints writing for magazines, and a manic-depressive temperament. Agee was known for standing about on Parry Street, a bottle cradled in his arms, talking to strangers. Having seen any number of talented folks squander their lives and talents on booze and other ‘dry goods’… well… I have my theory.

But in the end, there is That Book. To be able to do that! What an amazing thing. I doubt I will ever write as well as Agee, but he instilled in me, as a teenager, a desire to try. I knew the moment I read the book that here was something I could do for the rest of my life, something big enough, important enough to devote a life to. And once I sobered up myself, I’ve given it my all.

Dwight Garner, book reviewer for the New York Times is apparently working on a biography of Agee. I can’t wait. For those who might be interested, there is also this article by David Denby in The New Yorker from back in 2006. And of course, I can’t recommend Let Us Know Praise Famous Men highly enough, or A Death in the Family.

So that was my writer’s turning point. What was yours?

Copyright 2008 Lauren B. Davis For permissions: laurenbdavis.iCopyright.com