Betrayal of the Inuit

I have just finished reading Melanie McGrath’s excellent book, The Long Exile, and I was so moved by it I thought I’d write about it here.

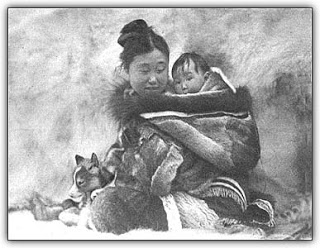

Beautifully written, poignant and engaging, McGrath’s book is at once horrifying and hopeful. Her descriptions of the Inuit relationship to place and their fierce will to survive, first, the harsh landscape they so love and, second, the idiocy, cruelty, racism, arrogance and “good intentions” of those whites they find themselves in contact with, are inspiring. (Although, at least in this reader, the book also invoked deep shame as a Canadian, and fury at the treatment these people received.)

This is the story of Robert Flaherty’s famous film “Nanook of the North,” and the child, Joseph, he fathered (but never recognized) while living among the Inuit. Thirty years after the film was released to mammoth acclaim, the Canadian government forcibly relocated three dozen Inuit, from the east coast of Hudson Bay to a region of the high arctic 1,200 miles farther north. Paddy Aquitusuk, Joseph’s step father was among them, and eventually he and his family followed, hoping to bring comfort to a distraught and lonely Aquitusuk.

Whereas the area they came from was rich in caribou, arctic foxes, whales,seals, pink saxifrage and heather, their destination was Grise Fiord, Ellesmere Island, an arid, desolate landscape of shale and ice virtually devoid of life, and certainly not the land of abundant game and spring flowers they had been promised. The most northerly landmass on the planet, Ellesmere is blanketed in darkness for four months of the year. There the exiles were left to live on their own with little government support and few provisions.

The reasons for the relocation were, in large part, political: Canada hoped the presence of Inuit on Ellesmere Island would discourage Greenland, Denmark or the United States from staking a claim to the island. It was also, though, intended to relieve pressure on the Hudson Bay Inuit population who, since their traditional way of life had been largely destroyed, were more and more dependent on the white individuals and institutions established there. The absurdly paternal whites believed it would be so much better for the Inuit if they returned to their traditional ways, without any thought at all for the survival-imperative generational knowledge of the land the Inuit would lose by relocation.

McGrath says of the Inuit relationship to the land:

“The land is a spirit to the Inuit, and everything in it is a spirit; they’re pantheists and they believe that very strongly. Their whole world view is so different to ours but it’s fascinating and we have a lot to learn from it. For instance, Westerners went merrily around the Arctic, naming places after famous people, but our names mean absolutely nothing to the Inuit who have their own wonderfully robust descriptions for every feature of the landscape, such as ‘the glacier where you can chip bits off but not very much because it’s quite hard’ or ‘the river where you can sometimes catch really big char but which ices over very early.’ All of that information enables them to navigate in a way which is much more knowledgeable than ours and makes us seem incredibly blundering and hopeless, which I think we are.”

The results of the relocation were predictable, although apparently no one did.

Forty years after the first families left Ungava for Ellesmere, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program. At its conclusion, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples called the relocation “one of the worst human rights violations in the history of Canada.” The country was shocked by the abuse and arrogance of its leaders, who eventually made financial reparations of 10 million Canadian dollars to the survivors and their families. But the government has yet to apologize.

One of the most poignant stories is that of Paddy Aqiatusuk, Joseph Flaherty’s step-father. Aquiatusuk was a sculptor of international acclaim, whose splendid work graces the shelves of a number of museums. Aquiatusuk, who knew virtually nothing about how famous he was, died of a broken heart on Ellesmere, “full of unknown spirits and unfamiliar stories.” How ironic it is that several months later, when news of his death reached the south, Time Magazine ran his obituary, albeit with the facts of his death wrong. It seems the world thought enough of him and his work to mark his passing, but not to honor his life by granting his request to go home. Joseph Flaherty was on his way to his step-father’s side, but Aquitusuk was dead before he got there. In turn, Joseph’s fate was just as tragic.

It is beyond me that the Canadian government doesn’t think these people deserve an apology. For what it’s worth, they certainly have mine.

A highly recommended book.

Harper apologized to the First Nations–but nothing has changed. Words aren’t enough.