David Blackwood dreams…. a Newfoundland history

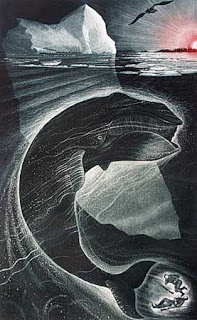

When I was in Newfoundland recently I came upon a book of David Blackwood prints. I’ve been a fan of Blackwood’s work for a long time. His images of whales in black, impossibly deep waters and men in impossibly small dories next to icebergs the size of skyscrapers; veiled mummers and steadfast grandmothers; lost ships, half-frozen sealers and half-forgotten dreams seem to be not so much images created by a kindred spirit which my subconscious recognizes, but as images born from my own unconscious. It’s visceral. It’s haunting. It’s lasting.

Fire down on the Labrador by David Blackwood

Fire down on the Labrador by David Blackwood

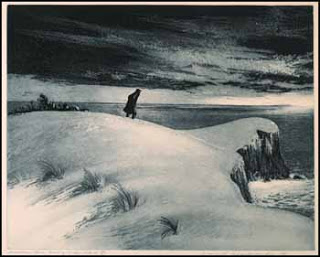

The Great Peace of Brian and Martin Windsor – David Blackwood

The Great Peace of Brian and Martin Windsor – David BlackwoodSurely this is the mark of a great artist – the ability to dive down into some salt-water collective unconscious and bring back to the surface universally recognized images.

Certainly that’s what writers dream of doing.

As a result of Blackwood’s images, there’s a story living in my head. In this tale a saltbox house floats upon North Atlantic seas, tethered to a long black dory. In the dory sit seven men, and none of them look in the same direction, nor do they look at each other. My perspective is of that of a sea creature just breaching the waves, looking up at this boat and those men and that house. Behind the boat the sun sets, sending long ragged blades of light against the prow. The men look cold, bundled against the slash of wind and spray. They do not look at each other. Each has chosen a particular and separate point in the middle distance and latched upon it, as though there is something shameful about dragging this house through dark water from its island nest to safer, tamer shores. Why is that, I wonder? Why shame? The sea is black, opaque, indifferent. The house is white clapboard and the front door is barred. Five windows reflect nothing but black sea and the memory of rain. The side door may not be a side door at all, but may be an interior door. Part of the outside wall – a porch perhaps — might have been sliced away to reveal that door on the wall of an inside room -wainscoting and wallpaper – vulnerable as the interiors of things always are. Above this ambivalent diorama is another window, but here the mullions form a cross, white as whalebone, as though the dead beg a blessing for the house that floats upon the sea.

I imagine the weight of the house, tilted slightly backward, resistant to change.

David Blackwood etched this image and called it Uncle Eli Glover Moving.

Mr. Malcolm Rogers’ house moored to the shore awaiting high tide, during the course of its relocation from Silver Fox Island to Dover, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland during resettlement. Photo: B. Brooks

Mr. Malcolm Rogers’ house moored to the shore awaiting high tide, during the course of its relocation from Silver Fox Island to Dover, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland during resettlement. Photo: B. Brooks This photo is as close as I could come to the Blackwood print, which is not on line anywhere that I could find. Perhaps this photo, or one like it, is what inspired Blackwood. Or perhaps it was the stories told over a mug-up in the kitchen of a house very much like this one, passed from the lips of elder to the ear of younger, ensuring they would never forget what it was like.

And what was it like, and what was the ‘it’ I’m talking about? Relocation, that’s what. I’ve spent the afternoon trying to figure out a way to explain it and in the end I can’t do it better than William Gough did, so I’m going to type the damn thing here and hope you will be as moved by it as I am — so moved that you’ll go and buy the book and any other book you can find by William Gough. I will preface it by saying that back in the day, when a man asked a woman to marry him, and she agreed, he began building a house for her. He and his fiancee would spend hours talking about their house– all those little details: where to put a shelf, where would the cupboards be, which way would it face, what color would they paint it. Imagine how much you would learn about a person over the course of this building time. Imagine how you would learn to compromise and communicate with each other. When the house was done, the couple would marry. All those hopes, and dreams, and sweat and toil, there in that house. The wedding night, the blood and the pain, pleasure and laughter. The babies born, and those who died. The bread kneaded and folded and baked, the cups of tea, the arguments and the settling. The bones and muscle and prayers… And then one day…

It was a dream of the province’s premier, Joey Smallwood, to stop the raggedness, the sheer disorder of people living wherever they chose to love and make their homes. No one on Bragg’s Island had dreamed the dream of resettlement. But, as a young man, Blackwood’s grandfather had encountered Joey Smallwood. Talk of confederation was everywhere at the time; David Gover was opposed to it, Alfreda in favour. One day while Glover and some other men were digging a well, he glanced over to see that his wife was standing watching them, a stranger at her side. The short, painfully thin man in the black suit and the trademark bow tie was identifiable at once as Joe Smallwood. But Blackwood’s grandfather didn’t pay much attention to the unwelcome arrival. It wasn’t until his wife approached and told her husband that Smallwood would like a ‘chat’ that Glover glanced over again. Then, instead of going over for a chat, David Glover looked back into the well that he and the other men were digging. Loud enough for Smallwood to hear, her replied, ‘We’re doing something important here, and I don’t have time to waste on politicians.’

The Smallwood government found it irritating, as the twentieth century marched on, to see a people who clung to land that was ‘inconveniently’ located. Once upon a time, doctors had been expected to brave the storms, fight the seas in all weather to help people on Bragg’s Island; now it was decided that was the wrong way to run things. People were to be moved to places where there were government services, instead of having th

e services come to them. Neat rows of figures in sharp columns on white paper laid the foundation for the plan. Men in shirts and ties schemed deep into the night inside their brick buildings, fluorescent tubes lighting their pale faces.Once resettlement was underway, the politicians came up with many reasons for people to move. “We can’t get you teachers, doctors, plumbers, electricity, or television here,” they said. “Come to us, and we’ll give you what you’re missing.”

No one had ever heard of such a thing as resettlement when young David [Blackwood] sat in the front of a motorboat on his way to Bragg’s Island, waiting for the first sighting of the warning light. “Then one night,” recalls Blackwood, “Gram Glover had a dream. I can remember her coming down to the kitchen that morning. “Well, well, well,” she said. ‘I had a funny dream last night, that we all had to pack up and leave this place. That we had to pack up and everything was torn to pieces, like there was another war coming. The whole place was in a shambles. There must be another war coming!”

“When the time came for them to be resettled, they didn’t shift the house, you know; they took it down. And my grandfather locked himself in his shed and wouldn’t come out. So his son started to take the house down; piece by piece, he took apart the house.”

As each board was pulled screaming from the wedding house, the house of the marriage bed, the birthing bed, the kitchen with the warm stove, the windows that had always seen the sea, Blackwood’s grandfather stayed locked inside his shed.

David Glover lived for years after that week, in a house in a growth centre. He sat and looked at the wall. The pole that had held the warning light was broken, the lantern gone, and an old man turned his back to the outside world in a house he hadn’t built.

If he had known that someday people would start to move back to the island, that there would be families who make the place a summer home and some who think to live there year round, David Glover might have stood and walked and found a boat, then pulled straight and true, hands huge upon the oars, angled as a gull heading back home towards Braggs Island.

As it turns out, there was one crucial factor the bureaucrats didn’t consider. There is something stronger than brick buildings, more powerful than columns of figures and forms filled out in triplicate. The bureaucrats dismissed Bragg’s Island, if they thought of it at all. But their calculations hadn’t included the boy who would gather the stories, the sounds, the sights, the memories of all who had lived on that one small island. Patiently, with great care, David Blackwood would reconstruct the world of his childhood on paper, drawing out the faces of those he loved, their eyes as they seek out our gaze, their hands as they reach towards us.

I hope William Gough won’t mind that I have reproduced his words here. I have done so as an act of respect to him, and to David Blackwood. In my last post I said that I would write a blog about the history of Newfoundland, which has so inspired me. I can do no more than quote those who understand it all better than I do.

the Que gov't relocated communities in Gaspe, from areas that are now provincial parks. the houses had to be left standing in their original place, so as to provide some "atmosphere" of how the place used to be. so you hike through now & see the old wooden houses up on the cliffs, with their windows boarded over & painted black. very strange.

I stumbled on your article while in the middle of writing about David Blackwood's work. What an amazing, haunting article, thank you for doing the research and sharing it.