Making Peace with the Writer's Mind

A few years ago I suffered a moderate depression. I get them now and then, and certainly I come by them honestly, as anyone who knows me can testify. Usually I go to bed for a few days and then shake it off, but in this case, after a month of lolling on the couch watching bad TV and mumbling about the pointlessness of all existence, my Best Beloved suggested perhaps I needed some help. And so, among other things, I sought out a therapist.

Well, not to besmirch the therapist, who was a lovely woman, but in my humble opinion she didn’t have much understanding of the writer’s mind. In fact, I eventually gave her a copy of Eric Maisel’s book, LIVING THE WRITER’S LIFE, in the hopes it would give her some insight. Her conclusion was that I identified myself as a writer too strongly and if I’d just give that up, then I’d be happier.

Alas, this is rather like telling a fish it would be happier as a bird, if only it would give up its pesky attachment to that whole water thing.

I didn’t go back. Instead, as is my habit, I plunged into the dark wood alone, and eventually found my way.

I don’t want to give you the idea that a writer’s life is one of unmitigated gloom, rejection and heartache. It isn’t. If you are so inclined, living your life as a writer is wonderful, and the gifts significant. To spend time thinking, reading, imagining is a blessing. Being able to touch people with your work, even just a few, is astonishing. Writing can be a meditative, prayerful, playful, exciting, glorious, illuminating activity. Paying close attention to the world and the people in it, as a writer is required to do if they want to write anything even mildly interesting, is deeply enriching and develops compassion, empathy and well… soul. Still, it can be hard, and that’s the part I’m talking about here. I’m sure I’m not the first one to mention that writers, perhaps more than other people, are prone to depression. Too much isolation, perhaps, or uncertainty, or criticism…

Part of my particular depression had resulted from a few professional setbacks, the sort all writers go through — problems with agents and publishers and rejection and so forth — as well as a good deal of stress brought on from a couple of major life changes. Emotionally, I was pretty worn out, and the idea of not being a writer anymore was quite attractive(and still is on certain bad days), but the problem was, try as I might, giving up writing made me far unhappier and more neurotic than ever before.

A writer is, in my experience, not necessarily someone who enjoys writing, or someone who writes well, or even someone who makes their living at writing. Rather, a writer is someone who is compelled to write, and cannot do otherwise. In other words, writing is a form of mental illness. (I do hope someone laughed at that. It does help to keep one’s sense of humor.)

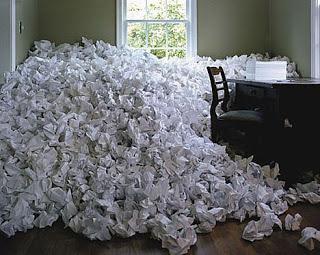

I have spent a great deal of time this morning ransacking my office in search of an article (from Psychology Today, I think) written in the 1950s by a psychiatrist who worked extensively with writers. I can’t find the bloody thing, in spite of having dumped out so many files that the rest of the day will be spent reordering them. If I do come across it, I’ll come back and properly reference it. However, his conclusion was that a writer should never try and give up writing, since doing so put her at extreme psychological risk. The medicine for the psychologically troubled writers is, apparently, more writing.

Eric Maisel says, “Probably the only thing that distinguishes the writer from the non-writer is that the writer is motivated or compelled to write and that she has taken the plunge and begun writing.” I almost agree. But, but, but…I have seen any number of people who are motivated and take the plunge, but few who continue year after year, rejection after rejection, heartbreak after heartbreak. A friend of mine, the wonderful writer Jeremy Mercer, wrote to me recently, reminiscing about the years we both spent in Paris. He said, “I can’t tell you how many self assured young men told me their novels would be taught one day–taught, if you can believe it. Now, hardly anybody from that scene is even writing, let alone writing historically important novels.” So, to begin writing isn’t enough; to keep at it because one cannot do otherwise, now there’s the meat of the issue.

Lots of people, it seems, want to be authors at one time in their life or another, but few want to be WRITERS. And that’s the difference between someone who wants to have their work published, and someone who is compelled to spend their days as Annie Dillard describes it in her book, THE WRITING LIFE:

It should surprise no one that the life of the writer–such as it is–is colorless to the point of sensory deprivation. Many writers do little else but sit in small rooms recalling the real world. This explains why so many books describe the author’s childhood. A writers’ childhood may well have been the occasion of his only firsthand experience. Writers read literary biography, and surround themselves with other writers, deliberately to enforce in themselves the ludicrous notion that a reasonable option for occupying yourself on the planet until your life span plays itself out is sitting in a small room for the duration, in the company of pieces of paper.

Hence, that period I spent on the couch obsessing about the pointlessness of it all. It would, after all, be much more useful to spend my days feeding the poor, sheltering the homeless, consoling the broken-hearted and protecting the vulnerable. And certainly I try to do at least some of those things, at least as often as I can, but in truth I find it impossible to stay sane and not to write. If a day goes by and I haven’t written anything I am fidgety, irritable, and filled with a sense of urgency that is akin to the compulsion I felt for a bottle of scotch when I was a drinking alcoholic. (Some folks say ‘practicing’ alcoholic, but heck, I wasn’t practicing — I had that down!)

So how, then, is a depressed writer to find her way out of the dark wood? Especially when vodka is no longer an option? Well, I’ve come to the conclusion that the dark wood may be the writer’s natural habitat, and so the question is, perhaps, improperly phrased. The question is not how to find one’s way out of the dark wood, but how to reside comfortably and usefully within its shadowed groves.

Eric Wilson wrote a book with an ironically bright happy-face-yellow cover called AGAINST HAPPINESS. In it he says this:

“Once we accept these seasons of mental winter as inevitable parts of our life–indeed, once we affirm them as essential elements of existence–then the paradox comes truly alive. We actually feel, in the midst of our sorrow, something akin to joy. I’m sure that we all have experienced this, that moment finally of giving over to our sadness, of not fig

hting it any longer. We then feel a strange vitality rise form the core of our very beings. We somewhere sense, probably deep in the unconscious; that we are now in our melancholia participating in life’s vital fluxes, in the profoundest forces of the earth. We suddenly feel better–not blissfully happy but tragically joyful. We die into life.”

A nice poetic piece of writing, that, as is his meditation earlier in the book on Melville. And what it boils down to is that the way to live serenely in the dark wood is by accepting it as one’s home. It is when we rush about, frantically trying to slash our way back to the sunny meadow that we find ourselves tangled in lethal, strangling vines.

The psychologist Otto Rank was fascinated by the creative personality. In THE BROKEN IMAGE, Clive Matson outlines Rank’s point of view (emphasis is mine):

According to Rank, not many people are prepared to face the challenge of themselves, to assume full responsibility for their own existence. Rank concluded that there were three levels or styles of response to this self-challenge. The first, and most common, was simply to evade it; the second was to make an effort at self-encounter, only to fall back in confusion and defeat; the third, and much the least common, was that of carrying the confrontation through to self-acceptance and new birth.

These three attitudes or approaches corresponded to Rank’s three types of human character: the average or adapted type, content to swim adjustively and irresponsibly with the tide; the neurotic type, discontented both with civilization and with himself; and the creative type, as represented by the ideal types of the Artist and the Hero, at peace with himself and at one with others.

Acceptance, again, it seems.

In Alcoholics Anonymous, the first step to recovery is to accept that we are powerless over alcohol. As a writer, I had to come to a similar conclusion: I must accept the writer’s life in all its guises. In other words, I have to do the work. I have to sit at the desk. I have to keep going, following one sentence after the other, without knowing whether it will lead me to a high-acclaimed bestseller, or a manuscript left unread and moldering in a drawer.

It takes a certain amount of perseverance, a certain amount of discipline, and perhaps a certain amount of madness. And I have to accept that, too. Just as I have to accept ALL the writer’s life — the joy of creating, certainly, the gift of experiencing the world with a writer’s awareness, and the occasional kind word and scrap of praise, but also the rejection, criticism, isolation and disappointment. A friend of mine, also a recovering alcoholic, talks about the simple things he has to do every day in order to stay sober. When he suggests someone else who wants to get through the day without a drink try the same things, and that person complains, he always says the same thing: “You don’t have to like it. You just have to do it.”

It does no good to tell a suffering writer to stop writing. Make her a cup of tea, instead; read to her, perhaps; make sure she eats a little; sit her by the fire, or in a sunny spot with a cat on her lap, and when she’s ready, put a pen back in her hand — that’s really the best medicine, since it’s her natural state.

It all comes round to that again, soft as breath, repeating endlessly: accept, accept, accept…

.

thanks, lauren, for every writerly word of this post — yours and the many others cited. if i were ever to get a tattoo, i'd be tempted to encircle the wrist of my dominant hand (holds the pen, yes, but so much more as well) with this: you don't have to like it, you just have to do it. wonderful.

Thank you for your post. I love to write and find it is very theraputic for me. I need to put my emotions, thoughts, idea on paper or into the computer. If they touch someone, I am happy!

I fight depression occasionally as well. My journals have gotten me through.

Cheers to you! Stay safe

Lori

Lauren–I love your blog. I want to collect these insights and bind them into a book! Maybe they will turn into a book one day. I'm supposed to be doing a day job at the moment, but instead I'm thinking about how I will possibly revise a first, yes, a first chapter after two years of struggling with the novel form. Shouting at it. Prying it open. Closing it again. Giving up and writing poetry. Writing prose poetry. It feels a bit pathetic, but there you go.

a