We don't do that here

Last week I was down in Trenton with an organization called People & Stories, a reading and discussion program that (according to their mission statement) “creates unique access to literature. Adults and young adults who have had limited opportunities to experience the power of literature work in small groups led by a trained coordinator. Participants draw upon their own experiences to discuss complex short stories. As they examine the poetics, issues, and values the stories explore, people can discover ways to see things differently.”

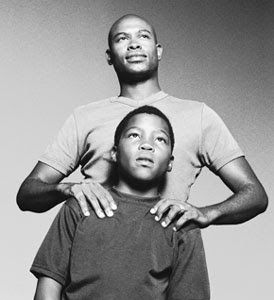

Now and then they ask me to join their classes and read one of my stories. The participants this time round were enrolled in a program called “Operation Fatherhood.” Fathers of welfare children, they are trying to leave street life behind and learn how to become responsible parents, wage earners, maybe even husbands. Most had been incarcerated at one time or another, some recently.

I like these men. They’re funny and smart and talkative, and their resilience is admirable. Okay, one guy got cranky when the organizer asked his name, promptly went to sleep and when he woke up halfway through the class got up and walked out without so much as a polite nod. However, the other guys made it clear they thought he was a jerk.

“Why’d he have to say it like that?” asked one young man.

“Like what?” I said.

“When you asked him if he was coming back, and he said, ‘hell, no.'” The young man frowned and cracked his knuckles. Disrespect is taken seriously here.

“He didn’t say, ‘Hell, no,'” I clarified. “He said, ‘I don’t know.’ Although, let’s be clear, I suspect he was thinking, ‘Hell, no.”

And everyone laughed then.

Sure, these guys done some things they’re not proud of, and have had some pretty hard experiences. One had been shot by someone with a .22 seven times, and when that didn’t kill him, the assailant went home, got a bigger gun and then ‘really lit me up,’ as the man put it.. I didn’t ask what had started the altercation. None of my business really.

What is my business here is trying to find common ground, to find myself in the experience of these men, and to have them find themselves in my experience, and in my writing. One man had apparently challenged the usefulness of such a program, saying he didn’t see how reading stories and talking about literature was going to help him get a job. I can understand his feelings, but here’s why I think this program is useful… let me give you an example….

Last year when I visited People & Stories, it was a few days after my brother Ronnie went missing. Ronnie was a drug addict and alcoholic who at 46 had been living with my father and step-mother as he tried to get clean… again. When he disappeared we all feared the worst, especially since my other brother, Bernie had killed himself a few years before.

The story they’d chosen for me to read that day was called, “Drop in Any Time,” a tale inspired by a home invasion that happened to a friend of mine. It’s a tough story, and upsetting, and I wasn’t sure I’d get through it, skinless and raw and scared as I was, so I told the class what was going on in my life, including the fact I was then clean and sober myself for a number of years, and asked them to help me out if I fell apart. Immediately, people were asking me if I was okay, and giving me hugs and asking if they could help and talking about suicides and addiction in their own families.

I got through the story and then we talked for about an hour. Without reservation I tell you that I got more compassion and kindness in that room than almost anywhere else. Why? Because they GOT it, and they aren’t afraid of pain, accustomed as they are to dealing with it, and they don’t shy away from the messy parts of life.

My brother’s body was found hanging from a tree down by the river a few days later.

Since then, I’ve written a story called “Neighbors” about a father dealing with his son’s death by drug overdose (because that’s how writers deal with things… we write about them) and it was published in a book called “An Unrehearsed Desire.” In the story the father goes to the home of the local drug dealer with a rifle, thinking to take justice in his own hands, although it doesn’t work out the way he expects (thank goodness). The men in Operation Fatherhood didn’t know why I’d written this story, but of the stories offered to People & Stories, that’s the one they chose to read. Hmmmm….

So, I told this group the history of the story and how this was going to be only the second time I’d read it publicly, and I hoped they’d have patience with me if I couldn’t get through it. And again they were kind and compassionate and they listened more politely than many of the audiences I’ve read for. When I was finished we talked about addiction and violence and dealers and how you try and protect your kids and clean up your neighborhoods. We talked about what responsibility we might have for our neighbors. One man talked about how impossible it was when one family teaches good morality to the kids, but then has to send them out into an environment where no one else gives a damn.

He’s right, of course, it is hard.

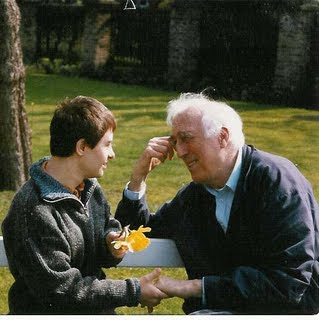

I remembered the story of Father Jean Vanier, who founded the remarkable l’Arche Communities wherein people with and without disabilities live together, sharing their lives as equals. In one of his books about the founding of these communities, he talked about a young man who came to live with them. He was in his early 20s. He was severely mentally and physically disabled — mute, deaf, blind, paralyzed — and had been cared for all his life by his mother, who had now died. Think about that. The only thing this young man knew was the scent and touch of his mother, who was now gone…and nothing could be explained to him. Not death, not change, not who these new people were, with the new touch and smells of a new place… how terrifying it must have been. And the young man began to make a noise, a terrible loud noise in this throat and he kept making this noise hour after hour after endless hour, from day into night and day and night again. In his hideous desperation, worn out and without a single nerve left, Father Vanier recalled wanting to go into the boy’s room and putting a pillow over his face until he stopped making that noise.

He didn’t. But the question Vanier asked was, why not? And he thought about the men he regularly met with in prison. Men who were convicted of murder, many on death row. He had always loved these men, as he believed God loved them, but a tiny part of his heart didn’t quite believe he was exactly as they were, for up until the moment this boy began making that terrible noise, he had never contemplated killing someone. But now he had. And so what stopped him from actually taking that terrible step? It was quite simple: in L’arche, they didn’t do that. It wasn’t possible. If he wanted to stay in this group, he could not do this awful thing. We don’t do that here, a voice in his head said. But in the world where the men convicted of murder had been born and raised, people DID do that. People were gunned down, stabbed, beaten with bats and bricks, with unspeakable regularity. In the world they lived in, murder was possible. It happened. In Vanier’s community it wasn’t possible.

Father Vanier understood that had he been born in a different place, raised in a different culture — such as the gang-banging, death-worshiping, nihilist, dog-eat-dog, turf war culture so many young people grow up in — he might just have acted on his urges.

I told the men this story, and they told me more of their stories and we talked about how we are the same, really, down in the marrow, full of brokenness and hope, dreams and despair and a great longing to be known, and touched by someone who loves us and cares for us. When the class was done there were hugs and handshakes and laughter and I know I felt that on this day literature had done a great thing — it had brought us together, people who might otherwise feel we had little in common. Prompted by literature we had made ourselves vulnerable to each other, we had showed each other who we were, and had been accepted. I think all our spines were a little straighter, our steps a little springier, when we left the room and looked forward to seeing each other again in a few weeks.

Taking that kind of risk with a stranger, and doing it with confidence and honesty, is just the kind of skill necessary not only for forming the bonds of community, but for getting a job, and keeping it, for stepping up and being a responsible, useful member of the world. So is being able to communicate effectively; to see the nuances in a narrative, either written or spoken; to present an argument, to find common ground, to accept compromise for the common good, to build a bridge between people…And so if ever anyone wonders if People & Stories offers anything to a man hoping to leave street life behind and become a responsible father, wage earner and husband, I’ll say, hell, yes. HELL, yes.

I’m honored they invite me, and deeply enriched for the experience. Thanks.

.

Lauren,

Great blog post and wondeful summary of our meeting. The title- "We don't do that here" has stayed with me since the class and it is such a poweful message for raising children, raising communities and holding oneself accountable. The men are excited about your next visit and I am too.

Talk to you soon,

stephanie