Death Be Not Proud

“Death is a test of one’s maturity. Everyone has got to get through it on their own. I want very much to die. I want to become part of that vast extraordinary light. But dying is hard work. Death is in control of the process, I cannot influence its course. All I can do is wait. I was given my life, I had to live it, and now I am giving it back” – Elegard Clavey

I’m probably not alone when I say death worries me. It always has. Even as a kid I would lie in bed, trying to imagine the moment of my passing, trying first to fathom, and then to tame, the excruciating inevitability of my own final moments. Panic and terror would rush in, as well as a horrible loneliness, and sometimes, just sometimes, a sense of peace, not unlike releasing a long-held sigh. A few times, I’ve lain in bed and thought, well, yes, if it were to come right now, if I were just to slip away, that would be all right. I’ve dreamed of my own death, and suffice it to say, I agree with Jane Kenyon when she says, “And God, as promised, proves to be mercy clothed in light.” But there’s no denying a fear of death as well, a sense of wishing it would be otherwise, a piercing agony at the thought of losing those I love so dearly.

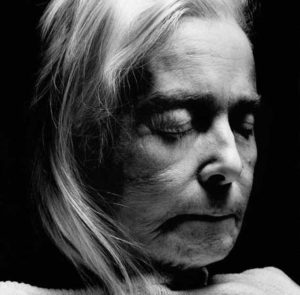

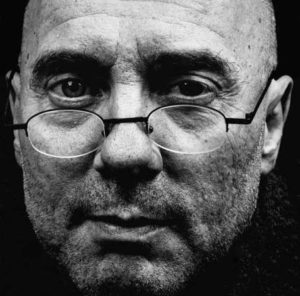

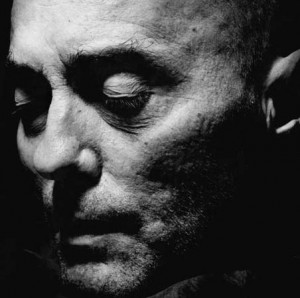

Obviously, I’m not alone in my contemplations of death. I recently came across an article about an extraordinary photographic exhibition on death and dying by German photographer Walter Schels. Due to the horrors he saw during the Second World War, Schels was terrified of death, and as he got older wanted to deal with this terror. Thus, he decided to take this extraordinary series of portraits of people before and on the day (just after) they died. His partner, Beate Lakotta, recorded the poignant and revealing interviews with the subjects in their final days. The exhibit will shortly be on display in London, but you can see some of the photos on the link above.

In the article, Schel and Lakotta discuss the loneliness the dying felt. In almost every case, they said, the dying felt abandoned by their loved ones, not because they weren’t there, but because they refused to accept their impending deaths. “You look great,” they’d say. “You’ll be home soon.” “Back on your feet in no time.” And so, in a very real sense, they were being forced to go through their deaths alone, and were grateful for Schel and Lakotta’s presence, because at least they could talk about the reality of the situation with someone.

No one smiled in the ‘before’ photos, although the photographer made no suggestion one way or the other. Dying is serious business, and the gravitas shows.

So moved was I by these photos, and by the accompanying article, that I posted a link on my Facebook page.

I was surprised by the response. A number of people posted directly to my page, still others emailed me. They talked about how angry the dying looked, how disappointed in life, how dreadfully lonely they seemed.

Yes, I could see that. But what surprised me was how the people who wrote seemed to be projecting onto these faces their own thoughts and emotions about death. The fearful spoke of fear. The disappointed spoke of disappointment. Some people spoke of intensity. Others of loneliness. Others of anger. But no one, NO ONE, mentioned the photos of the dead. What did they see there? How did it affect what they felt about the photos of the dying?

In each of the books I’ve written, people die. Often the characters I love most, and who are loved most by other characters, die. My new book, which will be published in the fall, OUR DAILY BREAD, certainly involves death (and cruelty in various forms, and what happens when we view our neighbors as Those People…as The Other). The book I’ve just begun working on is an allegory about the suicide deaths of my two brothers. With every book, death seems to nudge his way onto the pages, and I can’t help but wonder if, with every book, he’s taking up a little more space.

I think it’s safe to say, especially as I get older, that death has pulled his chair a little closer to where I’m sitting, demanding a little more attention. Fair enough.

The question of how one deals with death, the death of others as well as one’s own, is, after all, perhaps the ultimate question, since it defines the way one chooses to live. The Tibetan Book of the Dead says that we are here to train ourselves, to prepare ourselves, for the transition to come. Christianity says our deeds are written down and that we will be judged for what we have done, and for what we have left undone. One of my Jewish friends say there is no afterlife, and so we must do all the good we can here, because it’s the right thing to do, and because you want to lie in your deathbed content, before the great nothingness comes. I have another friend who is absolutely terrified at the idea of eternity, and prays (ironically) that there be nothing but a dreamless sleep.

For myself, I don’t know what will come next. A dreamless sleep doesn’t seem so bad, although my soul (or perhaps just my ego) longs for a transcendent reunion with The Ineffable, longs to believe I will go on to experience more wonders. I can’t bear the thought of death — not my own but the death of those I love — if they really are simply nothing. I can’t deny my relationship with my adopted father has vastly improved since his death (yes, you’re free to chuckle at that), and I feel much closer to him now, but that may just be my imagination at work.

But what did I see in those photos? Well, certainly a great searing loneliness in the photos of the living, and some anger, and some fear. But it was the photos of the dead which amazed me. I couldn’t put my finger on it at first, but then I realized that, had I not known they were dead, I would have thought they were people in deep meditation. They were, I felt, in some altered state, beyond peace, beyond contentment, beyond anything I’ve experienced, but it did seem to me they were experiencing something. And what came to me was John Donne’s poem, Death, be not proud.

As a slight aside, if you haven’t seen the play or the film “Wit” starring, in the film version, Emma Thompson, which tells the story of a Donne scholar dying from ovarian cancer, I suggest you rush off and see it. The question of whether there should be a semi-colon or a comma in the last line is transcendent. I agree with “Wit’s” protagonist that it should be a comma, for Death hasn’t the power of a semi-colon, no almost-stop, just a breath, a sigh, and then Death itself is gone and we are somewhere, something else. Perhaps that’s the best way of describing what I see in these photos: that “death shall be no more – coma – Death, thou shalt die.” And so, I give Donne’s poem to you here in that form. (Click here to see a clip of “Wit” wherein Thompson’s character talks about death, and not in the abstract, and click here for Thompson’s recitation of the poem.)

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful for, thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be ,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe go,

Rest of their bones, and souls delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy, or charms can make us sleep as well

And better then thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And death shall be no more, Death, thou shalt die.

Nothing but a breath, a coma, separates life from life evermore. I cling to that.

Lauren, thank you for this particularly moving essay. I followed the link and reviewed each of the photographs, then I read the article in the Guardian, then I watched the You Tube videos of WIT. The combination of these experiences, supported by your most thoughtful framing of this entire subject have touched my heart. When my time comes, I hope I’ll approach death as a comma.

thank you.

Incredible. This is so open, so packed full. I totally understand what you wrote about feeling closer to your adopted father, and I’m impressed that you shared that. Just went over to the photos. In some ways wish I had not, tho it is beautiful, fascinating, a worthwhile project. I have always been obsessive about death too. I wrote a “book” about it as a 7 year old. I finally realized only last year how much I suffer from compulsive, intrusive thoughts. Everyone has nightmares –awake and asleep–but I always had this background horror show going on, the constant and continual “What if?” worst-case-scenarios, the imagined scenes of murder and mayhem going on around me, and the sense that I should somehow be able to control it all if I thought hard enough about it. I absolutely relate to friend who is terrified of infinity. I often shoot out of sleep in the middle of the night gasping thinking about being dead forever. Dying is one thing, but being dead forever, the hugeness of the universe, time and space expanding and still still still being dead — it really physically hurts to think about. Thank you for writing this. Writing about these things is the only way to make them a little bit bearable.