The Spirituality of Imperfection

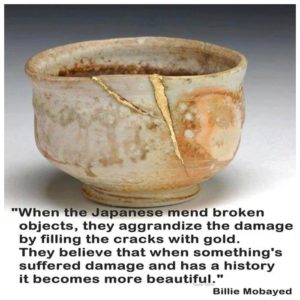

In the Japanese tradition of “Wabi-Sabi” that which is imperfect is considered deeply spiritual and beautiful.

I’m re-reading a great book right now, called THE SPIRITUALITY OF IMPERFECTION. Sounds tailor-made for me, doesn’t it? I know, I know.

This books speaks to me on several levels — as a person staying sober one day at a time, as a writer, and as someone seeking a closer relationship with the Sacred. In a nutshell, this book is about accepting the human condition, and finding meaning even within suffering. Not that suffering is required,you understand, but that suffering isn’t a sign of failure.

Those of us who live in the western world, particularly in the United States, often feel as though unless we’re happy, happy, happy, all the flippin’ time, that we’re doing something wrong.

A dear friend and I were talking today — she’s an actor and I’m a writer — about how things were going in our respective lives. I said I had just received a rejection letter from an editor that was so damn good I was tempted to use it as a blurb on the back of the book should it ever get a US publisher (it has a wonderful Canadian publisher.)

“What did the letter say?” she asked.

“It said, I’ve never encountered an account of alcoholism (in books or on film) that helped me to understand the disease quite so vividly. Still, for some reason they ain’t buying it!”

She laughed and asked why it was Canadian publishers were often more comfortable with this kind of novel than American publishers.

“Perhaps it’s that Northern thing,” I said. “Like Swedes and Norwegians, we’re more accepting of melancholy and of shadows. Not everything has to be bright and shiny. Although, look, the book does have a happy ending . . . ”

“But,” she said, “we Americans aren’t known for our patience, either.”

Snort.

Living with reasonable sanity as a writer — or living with reasonable sanity as anything, for that matter — requires a certain degree of comfort with ambiguity. As Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham say in The Spirituality of Imperfection:

“We modern people are problem-solvers, but the demand for answers crowds out patience — and perhaps, especially, patience with mystery, with that which we cannot control. Intolerant of ambiguity, we deny our own ambivalences, searching for answers to our most anguished questions in technique, hoping to find an ultimate healing in technology. But feelings of dislocation, isolation, and of off-centeredness persist, as they always have.”

And so, they go on to say,

“Spirituality hears and understands the pain in these questions, but its wisdom knows better than to attempt an ‘answer’. Some answers we only find; they are never ‘given’. And so the tradition [of spirituality] suggests: Listen! Listen to stories! For spirituality itself is conveyed by stories, which use words in ways that go beyond words to speak the language of the heart. Especially in a spirituality of imperfection, a spirituality of not having all the answers, stories convey the mystery and the miracle — the adventure — of being alive.”

And so, even if not everyone ‘gets’ our work, even if we don’t get what we think we want, we rest in the miracle and the mystery, and that is enough.

Lauren, I don’t think you could have found a better image than the repaired Japanese bowl to go along with this moving essay. Life leaves its marks on us, and there are many lessons to be learned along the way. As you quote above, some asnwers only the individual can find for themselves.

It seems like you’ve gained a balaned perspective on the rejection a writer often has to contend with as part of the writer’s life – is it a struggle?

Kind regards, Barbara

Hi Barbara — thanks for the comment. Is it a struggle to find and maintain a balanced perspective when it comes to rejection? HELL yes. Brutal. But that is part of the writer’s life, and if one can’t deal with it, one should do something else. It never ends, no matter how ‘successful’ a writer is. Because it is such a subjective field, here is always someone more than willing to tell you they don’t like your work. So be it. I write because I wake up in the morning feeling urged to do so, and because I am saner when writing than when not writing. So I continue. If ever I wake up and feel differently, I’ll stop writing.

Having said that, the knowledge is hard-won. I went through a very difficult period of near-universal rejection (for OUR DAILY BREAD, which later went on be nominated for the Giller, and for another manuscript that remain — for the moment — unpublished) and fell into a terrible, lengthy depression. It was in the depth of that depression, however, that I realized the only way out was surrender and acceptance: either I was going to keep writing regardless of the agony of harsh criticism and rejection, or I was going to stop. Since I didn’t seem able to stop, best to just get on with it. Honestly, that changed a great deal for me, psychologically and spiritually. Do I still have painful days? Of course, but I accept that as part of the writer’s life and surrender to the act of writing anyway.

Thanks for asking. You got me thinking this morning! 😉

Hello Lauren,

I very much liked your essay, thank you. Your response to Barbara Revell above added a level of personal experience which makes your essay all that much more poignant. I appreciate the honesty and clarity of thought and purpose you are so consistently willing to share with us.

Thanks so much for commenting, Donna. It’s very kind of you to take the time.

I love this, the idea of cherishing the wounds and, rather than hiding them, as we do in our culture, or living shamefully with their visible signs, filling them with gold. Can you imagine? Every fracture in our lives cherished, healed with gold. Beautiful.

Thanks, Mael. Although I wrote this piece some years ago, my confidence in the perspective grows. I have since repaired a broken piece of beloved china using the kintsugi method. It was a remarkable process of patience, acceptance, self-forgiveness (I was the person who caused the damage), and transformation. Such a powerful metaphor.