The Anglo-Saxon Forced March Northwards

With the publication of AGAINST A DARKENING SKY, people have been asking me to pull together the blogs I wrote on my research trip to England, back in 2008. And so, here you go… an account of what My Best Beloved calls, “The Anglo-Saxon Forced March Northwards”. I must say, reading these again has brought back a lot of wonderful memories, and much gratitude to all the people who helped me so much. I can’t believe I first started working on this book seven years ago!

BURY ST. EDMONDS AND SUTTON HOO

Written September 27, 2008

My Best Beloved and I are in Bury-St.-Edmonds, where, indeed, St. Edmonds is buried in the great cathedral. We are tired, and a bit footsore, and looking forward to a good curry, a bath and a good night’s sleep before heading up to York tomorrow.

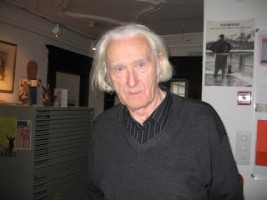

My last day in Zurich was sublime since it began with croissants and coffee with Fritz Senn, a most charming man, at the James Joyce Foundation in Zurich. Herr Senn looks exactly the way you’d like a Joycean scholar to look – long white hair, and those wonderful Gandalfian eyebrows some men of a certain age have, above mischievous eyes with only the faintest trace of sorrow.

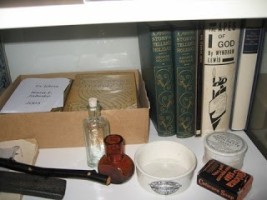

He and his colleagues, Ursula, Ruth and Tanya are without doubt the friendliest people I’ve ever met in Switzerland. The foundation is on the top floor of a slanted old house on Augustinegrasse in the old section of Zurich. The floors are so tilted that if you sit in a chair on rollers, you’ll make great use of them, rolling across the floor until the wall stops you. But it’s a great wall, full of books, and so your journey will be worth it. There are a number of treasures housed in these rooms, including a couple of Joyce’s suitcases, pipes, canes, and wonderful photos.

After this second visit, I feel I’ve made friends in Zurich, and that’s entirely down to Fritz, Ursula, Tanya and Ruth. I have the feeling anyone lucky enough to have the chance to visit them would walk away feeling exactly the same. Makes me want to go home and read passages from Finnegan’s Wake again, especially since Fritz assures me NO ONE understands the terrible, beautiful, frustrating, splendid thing.

Yesterday found us in the stunning Tudor home of Eileen and Roy Thomas, in Woodbridge, Suffolk.

We went to the great Anglo-Saxon burial site at Sutton Hoo. It’s a mystical place, with great mysterious mounds spotting the gently sloping meadows leading to the Deben River. Nick and Jackie Wright met us there and gave us a fantastic tour, and because Nick’s a guide with the National Trust, we were permitted free access to the mounds themselves.

I haven’t completely sorted out my emotions about the site, and so I’ll wait to discuss it more at a later date. But there is definitely something special about the place. Once the hallowed burial grounds of pagan aristocracy, later, during early Christian times it was used as an execution site, where the bodies of the executed were dumped unceremoniously in holes, left to flounder eternally in what the rather silly Christians apparently thought was an evil place. I disagree. A sense of the holy is everywhere there.

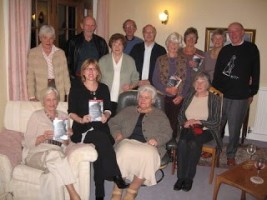

Last night I had the great good fortune to meet with Roy and Eileen’s reading group, who had recently read The Stubborn Season. I can’t recall a group that met me with such enthusiasm or with such intelligent questions. I am most grateful for the chance to meet everyone, and have a number of sources for my research, including Jenny and her work on estuary birds, Nick and Jackie, and lots of other names and leads for Anglo-Saxon history.

Book Group at the Thomas’s

And so, this morning it was on to West Stow, where there is a recreated Anglo-Saxon village. Here Lance Alexander, the Heritage Officer gave us an incredibly helpful personal tour, even though it was his day off. Lance is delightful in every way, and without his knowledge I suspect I would make any number of silly mistakes. Like what, you ask? Well, like rabbits. Apparently there were no rabbits in English in the 7th century. Note to self — rewrite Chapter Three, and think stoats, or weasels, but NO Rabbits!

The village itself – a number of thatched-roof houses, a hall, workshops, gardens and animal pens – reminded me so much of First Nations villages in Canada that, for a moment, it was a bit disorienting. The buildings flow organically out of the landscape and seem a graceful extension of it. All materials are, of course, utterly natural, hand-made, and of extraordinary delicacy and elegance. Even the willow hurdles around the pig pens are beautiful. There was a hominess, and undeniable air of welcome. It’s easy to envisage the family halls in the evening, with the glow of the tallow lamps and the flicker of the hearth fire making the figures on the tapestries seem to come alive. The sound of the lute, laughter from those listening to the scop tell well-known tales and riddles, voices raised in song, the lowing of the beasts.

All was not, of course, so picturesque. Famine, bone-crushing work, plagues of various sorts, unfair taxation from merciless kings – life was hard and exhausting. Still, as Lance took us into the weaving hut, with five standing looms leaning up against the walls (which would have been taken outside into the sunlight in fine weather), each with a stool in front of it, and skeins of colorful plant-dyed wool hanging all about, he had us imagine the gossip and chatter of the women who would have worked long hours here, since cloth for a single garment took six hundred (!) hours of work. I could almost see them, hands tapping the weft and weave, pressing shuttles through the threads, teasing each other, sharing secrets and tips for healing herbs and jokes about which young man might soon ask for a girl’s heart, which woman had the look of a baby on the way. . .

So much inspiration to be found everywhere, and when it’s all done for the day, a lovely cup of tea and a shortbread biscuit. Hard to ask for more. This is surely one of

the loveliest things of a writer’s life – to be able to follow one’s curiosity wherever it might lead. I have no idea how this story of an Anglo-Saxon woman trying to find meaning in a violent, unsettled time will finally turn out, but what a privilege to be able to follow the path through the woods and find out.

IN YORKSHIRE

Written October 2, 2008

My Best Beloved and I are in the Yorkshire moors and after a day of climbing about the ruins of Whitby Abbey on the wild, windswept headlands, I am exhausted and exhilarated at once. We drove up from York yesterday — and I’ve yet to write about that fantastic experience, although I will in the next few days (thanks John Rushton and Christopher Nolan!)

One of the books I’ve brought with me is Philip Newell’s CHRIST OF THE CELTS. In this book he says, “In the Celtic tradition, the Garden of Eden is not a place in space and time from which we are separated. It is the deepest dimension of being from which we live in a type of exile.” As I read these words, I remembered an apple orchard where, as a child, I had an early sense of sacred presence. It was a much neglected old orchard where no one but I ever seemed to go. The grasses had grown long, and the trees where gnarled, the air fragrant with apple blossoms in the spring and with the heady scent of rotting groundfall apples in the autumn. There was a little stream that meandered through the grasses, not much more than a trickle in the hot dry month of August, but in May and June it was a joyous, gurgling, burble. I spent more hours than I can count dawdling about in that place, dreaming the dreams of a young girl, watching the clouds, picking buttercups and reading.

I still remember the grief, futility and injustice I felt the day the bulldozers moved in, plowing down the trees, stopping up the stream, to make way for a row of spectacularly ugly town houses. No, more than remember that flush of anguish, when the thought of that morning crosses my mind, I FEEL it again. However, close on the tip of that dragon’s tail, is an instant recognition that the orchard exists still, right here, inside myself. I needn’t even close my eyes. It’s all around me, even as I sit in this charming room in the middle of the Yorkshire. I can feel the grass around my calves, the roughness of the tree bark, the coolness of the water in the stream. I can smell the rich smell of decaying apples and hear the lazy drone of wasps. The sky is blue, the robin is in her nest and her song mingles with the chirp of the sparrows, and the rustle of leaves in the warm breeze. The air holds the promise of rain tomorrow. The orchard is complete and alive and undeniably real.

Because I have loved that orchard, and because I felt something sacred there, it has become an eternal place, reminding me of that sense of perfect belonging, that perfect sense of ‘home’ I felt when I was there as a child.

I have found a few other places like that over the years. A garden in Normandy. A hillside in Wales. The ‘burren’ in Ireland. And now, today, I have found the Yorkshire moors. There is something undeniably mystical in the great, rolling land, equal parts sky and hill. The majesty is intense, and so is the beauty. I can only imagine what it might like when the ground is an exuberant riot of purple when the heather bloom. As we arrived on this landscape I felt as I have done over the years from time to time – this concentrated sense of coming home. Landscape, for me, is intricately tied to spirit, and some much more than others. I seem to have little control over it. For example, I would have loved to have felt that way about France, but somehow I never did, even though from an intellectual point of view I completely understood why others felt the way they did about that lovely land. It just wasn’t one of my soul homes. This is.

I wonder if that’s part of the reason I’ve been drawn to write this novel of this place set during a time of powerful spiritual forces? Perhaps. I discovered today, from a lovely man in the visitor’s center of Whitby Abbey, that Hild’s original timber monastery was built on the site of a much older pagan settlement, which contained a recently discovered iron-age round house, facing east. It is speculated this site had been holy for long, long before Christians appeared on the horizon. This seems to me perfectly reasonable.

Hild came because God, the Sacred, the Holy (whatever you wish to call it) was particularly accessible here, in this place. As Sister Rita, my fabulous spiritual director, often says – “why not go where God is?” This is not to say, of course, that the sacred is not everywhere, always, in our time as well as in sacred time, but rather that some places speak to some people with a little more clarity. Who knows why? Who cares? I, for one, am just profoundly grateful to be able to enlarge my internal landscape in this way. No matter where I travel, no matter how confined the space, these grand, awesome, soul-inspiring vistas will always be with me, reminding me of what it is to be home.

IN YORK

Written October 5, 2008

I said I’d come back to York, and I’ll do so now, from a very strange hotel in Hartlepool (more on that below)

So, York. Arriving, we took a bus from our hotel just up Tadcaster Road, into the walled center of town. A last gasp of warm weather and sunshine had called the entire county to the shopping district, and the added attraction of an international food fair compounded the problem. We caught a bite to eat and tried to wander a bit and get our bearings, but the crowds were tiring, and I am never good at crowds. Having to dodge baby buggies and gaggles of squawking, brightly festooned girls and boys, all waving cigarettes about, forced us into one church after another – sanctuaries indeed. The thick, cool stone walls, the dusty, damp air full of floating dust motes and the scent of candle wax, and the placid expression of the saints both painted and sculpted, all created a soothing atmosphere and soon we were ready to tackle the snickleways, as the tiny meandering lanes are named. They are more tourist traps now than the undoubtedly malodorous, unhygienic, poverty-stricken and dangerous passageways they once were. Still, they are almost ridiculously atmospheric, and one can, if one squints slightly, imagine how the town might have looked in medieval times.

The next day we met with Katherine Bearcock, curator at the Yorkshire Museum. Katherine was a wonderful source of knowledge and very kindly took us down into the basement of the museum and allowed me to handle a number of Anglo-Saxon artifacts, including a magnificent cruxiform brooch. We had a long chat about money during the 7th century, when in fact there really wasn’t any. I am still struggling with exactly how, if you were a noble person, you might purchase something at the market. that caught your eye – a young servant girl, for example. I mean, a seithkona (seeress) attached to a royal family is hardly likely to be dragging a pig around behind her for barter, is she? Well, maybe she has someone dragging about the livestock for her. We’ll see.

Next, it was off to the great Minster, where there were, thank heaven, considerably smaller crowds than the day before. York is a city built on a city built on a city built on a city, as most cities are, of course, but because this one seems to have been built as much on sacred foundations as secular, I do find it quite fascinating. I won’t go through all the various levels of kings and archbishops who made York their home (mostly because I can’t quite keep them all straight, frankly) but I do want to talk about the idea of historical, symbolic layers.

The more I travel about the countryside talking to historians and archeologists, the clearer this idea becomes. I think of it as a sort of plumb line through time, in spots where perceptions of the sacred reside.

At the York Minster (where My Best Beloved and I were treated to a phenomenal tour with John Rushton), we had a special treat. York Minster, seat of the Archbishop of York, was built in stages from 1220 to around 1472. One of the most famous stained glass art works is a painted pane depicting a wren attacking a spider in its nest. It dates back to the 15th or 16th century. In a 1988 New York Times article, Peter Gibson, the superintendent of the glaziers’ trust, who started as an altar boy when he was 12 and has been working on conservation of the windows since 1945, explained that he discovered this particular piece during his apprenticeship “in a completely misplaced position” and so he moved it to the Zouche Chapel (named for Archbishop William La Zouche, 1342-52). Here, he placed it in an outside window, eventually to be surrounded by other depictions of birds and animals. I’d come across the story of this window as part of my research and when I asked if it might be possible to be admitted to the chapel, a guide kindly ushered us in and then left us to discover the glass on our own. A great gift.

The Zouche Chapel seems a world away from the rest of the Minster, with the flocks of tourists, and great stadium-sized stained glass windows – all terribly beautiful. Inside the chapel’s heavy wooden door, one walks down a few steps, and the world is suddenly very far away indeed. The windows are all panes of individually painted glass, and there are a dozen or so rows of wooden pews facing a simple altar. After saying a prayer at the rail, I was drawn to a corner at the rear of the chapel wherein stood a stone shelf and a bucket on the floor. Approaching, I saw it was a well, with a bucket on the floor nearby. I was drawn toward it and stood for a few moments with my hands splayed out on the top of the wooden well cover. I had a great desire to curl up in this spot, rather like a window seat, and take a nap – most interested as to what my dreams might be. In short, it seemed one of those “unusual” spots, and I asked Ron to take a photo of it. Later, we popped into a little bookshop that had an intriguing litho by Arthur Rackham (from “Undine”) in the window. (Soon to hang in our bedroom.) As I flipped through other lithos, I came across a rendition of the very corner of the chapel that had drawn me. It was called “St. Peter’s Well,” and further research informed me it is the well where by tradition King Edwin was baptized by Paulinus on Easter Eve, 627. ‘In York Minster there is a well of sweet spring water called St Peter’s Well ye saint of ye Church, so it is called St Peter’s Cathedral’ — Celia Fiennes, “Diary in Old Yorkshire”.

It seems this was a long-established holy well, and in fact such holy wells abound in the area. The next day we came across another one in the village of Lastingham, where the 7th century church established by St. Cedd (with its astounding crypt!) stands next to a holy well inscribed with his name.

And sure enough, today in Hartlepool, where we spent the day with the Reverend Jonathan Goode and archeologist Robin Daniel, we found there is yet another well, that of St. Helen (mother of Augustine) just at the parish line from the community established by St. Hilda. Here, Robin told me, there was probably a bit of resistance to Hild’s community, which set up on a typically Saxon hill, a beacon to all (much as the original Roman signal out on the tip of the headland) and ignored the un

doubtedly already locally revered holy well.

There’s much to consider here. Again, I am struck by how seemingly organically sacred places are recognized by all such inclined people, regardless of what label they wish to apply to it, or what new rituals they may desire to perform there.

It appears that while the arguments of religion will never end, we continue to miss the point, which is, as far as I can see, very close to what T.S. Eliot said in Little Gidding (which was placed at a prayer bench in the crypt at St. Mary’s church in Lastingham):

If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosityOr carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

And what the dead had no speech for, when living,

They can tell you, being dead: the communication

Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.

Here, the intersection of the timeless moment

Is England and nowhere. Never and always.

Eternal moments. We’re always struggling, it seems, either with them or toward them.

There were other fabulous moments in both York and Hartlepool. Christopher Norton, an archeologist who specializes in medieval York, joined us for a chat and one of the very best cream teas I’ve had since being here. We talked at some length about what York looked like in the time of King Edwin, where the original chapel might have been built, how the rivers were used, what might have been left of the Roman fortress and living quarters on the other side of the river, and what might have happened to the deacon James, after Paulinus went back to Kent… A wonderful conversation with a lovely man, and I was charmed to meet his wife, Sue, an Anglican priest, as well.

In Hartlepool we were met by Johnathan Goode, rector of St. Hilda’s and Robin Daniels, the archeologist who has done so much work on the site. Jon, as the good rector prefers to be called, isn’t quite what I expected in a northern vicar – longish brown hair he often flips back off his high forehead, a pea jacket in need of some repair, jaunty scarf, tee-shirt, jeans and big black boots, he looked more like a 1960’s Newcastle musician than a stuffy old vicar – and indeed it turns out he’s a great fan of old Stax Records R & B. He couldn’t have been more fun, and is one of the most passionate people I’ve met in a long time – with a true dedication to the people he serves. He began as a social worker, working with the homeless and the addicted, and became a Christian, he says, became he realized he wasn’t relating to his clients as real human beings. Christ, he says, taught him what it meant to truly care for others. He’ll be leaving St. Hilda’s in a week or so and Hartlepool will miss him. Newcastle, however, will be lucky to have such an energetic, committed priest.

Robin Daniels, archeologist, Lauren and Rev. Jonathan Goode in St. Hilda’s with a 7th c. grave marker. (Photo: Ron Davis)

Rev. Jon toured us round the church, pointing out a beautiful Anglo-Saxon gravestone, one of a very few from the period. Robin told us they were actually mass produced, probably at Lindisfarne, with the engraving of the cross, and the symbols for alpha and omega coming with the stone, while the name of the deceased, carved in Anglo-Saxon runic letters beneath, was clearly done, in rather bad lettering, by someone local.

We had lunch and talked about faith and authority (particularly how difficult it is to deal with sometimes) and class injustice and how hard it is to do the right thing. Just the sort of chat to help fire up a writer’s imagination.

Then Jon left us as there was still much packing to be done before his move, and Robin took us out onto the headland proper for a tour of the site where the original monastery and later Hild’s monastery would have been. He also had some fascinating facts about that well, St. Helens, just at the parish border line, and we wondered whether this might have been an older, local sacred site, which perhaps caused some friction with Hild when she popped up with all her new-fangled Saxon ideas about great churches on hilltops, rather than humble wells devoted to gods old and new. Robin also talked about how lovely the timber houses of the Anglo-Saxons were – of whitewashed wattle and dab, possibly decoratively painted inside, hung woven panels and quite snug. . . not the mud and shit-covered wretches so many people think lived in the era. Again, more stuff for the writer’s imagination!

Lauren and Robin Daniels at the sea landing in Hartlepool, the site of Hilda’s first monastery. (Photo: Ron Davis)

And then, frozen to the bone, it was off to the “Grand Hotel.” It’s not terribly old, by English standards, just over one hundred years, and recently refurbished, which I think means some really bad modern furniture’s been moved in. The plumbing seems unchanged. Its halls were alarmingly dark, as is the lighting in the room, and the stone-colored walls and grey carpet didn’t help much. However, I feared it wasn’t the sound of our neighbors having a good old “knees-up” next door, or the garbage bins down below slamming shut, the fairly frequent sirens, or the bass thumping up from the party in the sparkly Victorian ballroom. No, earplugs would probably handle that. But what do you do about, well, certain… how do I put this without sounding like even more of a nut that you might already think I am? Energies? Okay. Let’s call the chain-dragging, walking-through-wall, moaning in the dark things energies, shall we? And no, I didn’t actually see any of those things, but the last time I felt this way was in a hotel in Florence where I kept waking up all night long and finding strange people in the room who disappeared every time I moved to turn the light on. Okay, just an undigested bit of beef, you say? Possibly. But I took a sleeping pill just in case.

There is a sort of sadness about Hartlepool, the same sort of sadness I’ve seen in many rust-belt towns, when the industry has moved out, or the mill shut down, or the fish have been fished out. A lethargy, and a sort of shambling ill humor. There are shades of its once impressive glory in the old facades, but the people don’t seem terribly cheery and I must say there were a rather disproportionate number of hangovers among the hotel staff on Saturday morning. In fact, it seemed a good number of the staff didn’t bother to turn up and called in ‘sick’, although the one waitress who was frantically trying to manage alone, said she’d heard they “were out on the town” last night.

I’m sorry, in thinking about this, that Rev. Jon has been forced to move on, while the parish is downgrading to half-time priest. This is a very special church, with a very special history, and although I know medieval churches are thick upon the ground in this part of the world, and probably the people here don’t have the money necessary to keep it up, still isn’t that all the more reason to keep a full-time presence there? The people who greeted me at the church before Rev. Jon and Robin arrived, who made Ron and me tea, and made us feel welcome, were a real community, kind as milk, and they obviously care deeply about this place. That sort of thing can spread out into a community if it’s allowed to, and isn’t that the job of the church, after all?

BAMBURGH, YEAVERING AND HOME AGAIN

Written October 12, 2008

The ends of trips are, like any liminal states, difficult both to navigate and describe. There’s the physical stuff, of course – mounds of laundry, stacks of mail, all those must-do things that had been put aside for the trip, like washing the windows, getting the fireplace cleaned, writing the press releases for upcoming reading events, dealing with the wonky burglar alarm. And there’s the jet lag – strange dreams of unknown cities and waking up at odd hours, a vague nausea, an off-kilter appetite. But it’s the emotional weirdness that, for me, is the most disconcerting. It’s a sort of combined restlessness and grumpy fatigue, a desire to pull the covers over my head while feeling at the same time that if I don’t get EVERYTHING IN ORDER right now, somehow I’ll never catch up to myself.

So, small steps. Throw in the first load of laundry. Have a cup of coffee and a poached egg. Make the bed. Try and ignore the hideous news reports. (The video circulating of a McCain supporter holding a monkey doll with an OBAMA sticker wrapped round its head is enough to make me want to run back to the moors!)

Part of this liminal state is looking back at the somewhat frantic last few days of the “Anglo-Saxon Forced March Northwards” and attempting to put it into some kind of order.

The last place I wrote about being was Hartlepool, I think. From there we went to Jarrow, for a quick trip around Bede’s World, a wonderful site dedicated to The Venerable Bede, and a long drive through horizontal sheets of rain so that My Best Beloved could find Hadrian’s wall. We did pass an inordinate number of lovely stone walls, some of which I was quite sure would have contained at least some portion of the stones originally used on Hadrian’s wall, but no matter how frequently I pointed these out, My Best Beloved was not content until he found an actual part of the wall and stood upon it. The fact that this was accomplished by driving down a road clearly marked “Do not drive down this road” and which entailed a rather harrowing twenty minutes along a ridiculously narrow and occasionally flooded mud track, a 27 point turn and a face-to-face with another disgruntled motorist, in no way deterred my intrepid Best Beloved, bless ‘im.

We also passed this interesting spot on the drive. It is a natural formation, not a great burial mound as I first suspected, and was sacred to the Anglo-Saxons. If memory serves, it was known as Frige’s Hill. (If I’m wrong about this, feel free to correct me.)

And so, at last, we found out way to Bamburgh and Budle Hall, the rather eccentric bed and breakfast where we lodged. Run by two very kind people, Sue and David, in a fabulous, if somewhat run-down late Georgian Manor, we were treated to fine art on the walls near the remarkable floating staircase, bright plastic ‘grass’ dividers on the breakfast table, stunning bouquets of fresh flowers on the mantle in our room, fairy-lights and Indian hippy-ish cloth on the mantles in the living room, bright green carpet and oranges walls, bathtubs in need of a good scrub, very loud opera music one night (and very loud Abba music the next) combined with a television set tuned to the BBC (both courtesy of our hosts), no locks on any of the doors, and no numbers either (which led to an embarrassing moment when I couldn’t remember which room we were in and thus met a very nice couple who weren’t exactly expecting visitors), and an absurdly bucolic view of sheep and horses in the rolling fields, straight out of Jane Austen.

I haven’t quite made up my mind about the place. But doubtless it will feature in a short story sometime soon.

One of the first things we did was take advantage of a beautiful sunny day and head out to the Holy Island at Lindisfarne. This is where I learned about the importance of paying attention to tides. The only way to drive to Lindisfarne is over a causeway which, like that at St. Michel’s in France, is tidal. Low tide you’re clear. High tide you swim. So we dutifully checked the tide schedule and saw we were safe between 9:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. Loads of time.

Arriving at the island, we parked in the car park and wandered past the rows of picturesque cottages into the center of town where the ruins of the priory are. From there we visited the graveyard, naturally, and headed down to the shore. Lindisfarne was a monastery founded by St. Aidan, who came to the area from Iona at the request of King Oswald in the early 7th c. Both Aidan, and later Cuthbert lived on a tiny hermitage island which at low tide is accessible from Lindisfarne itself. Ron and I walked across the mussel-shell and sea-weed covered rocks to get to the tiny hermitage. The outline of a small stone hut survives, and is marked by a cross.

We sat on the rocky cliffs, watching the sun on the water. Far out on a sandbank, hundreds of seals basked, and from time to time their heads popped up quite near to shore. Three woman sat nearby, who had come to Lindisfarne on a retreat, and they sang songs in soft high voices, to the seals. We could have stayed for days. And nearly did.

After an hour or so, I stood up to stretch and further investigate the monk’s cells. This is when I noticed the rocky path we’d followed to get to the island had disappeared under a rapidly-deepening band of water. You’ll pardon the expression, but holy crap!

I called to Ron, and then to the three women, one of whom was probably in her seventies, and we headed for the water. There was nothing to it, but to take off our shoes and socks, roll up our pants and wade for the shore, and quickly. I noticed a coast guard jeep had arrived on the far shore, lights flashing, and that a small crowd had gathered, but no one seemed in the least inclined to wade over with a pair of Wellingtons. I set off first, and let me tell you, the water was icy cold and the mussel shells painfully sharp. My Best Beloved waited a few moments and at first I thought he was waiting to help the other ladies across, but then realized that although this may have been part of his plan, he was also waiting to get a good photo.

I made it to shore, a little shaken and footsore, quickly put on my socks and shoes, and ran to the coast guard to ask if anyone had boots I could take back for the elderly lady. No lucks, although judging from the laughter this was apparently quite a funny question. The elderly lady, as it turns out, was extremely game and all thr

ee, and Ron made it back no worse for wear, and a little excited by the adventure. The coast guard’s job apparently, is to drive down to the island, laugh at the trapped tourists, smoke a cigarette, take our photo, and go home for tea. We found out that last year someone had spent nine hours trapped on the island. It seems the tide comes in here at least three hours than it does on the causeway – although this information isn’t marked anywhere. Consider yourself duly warned should you ever head for Lindisfarne. I will say, however, that the hour or so spent communing with the sea and the seals was worth the bruised, frozen feet.

Safely on the right side of the Lindisfarne tide. (Photo: The Coast Guard, which is pretty much all they did to help!)

Bamburgh castle and the surrounding area are insanely atmospheric and it would be impossible not to write about it. In fact, I’m rather surprised everyone who lives there isn’t madly scribbling. From the brooding, still inhabited, castle on the cliffs at the edge of the sea, which dates back, it seems, to the Iron Age, to the nearby Cheviot hills, where another Iron Age fort once stood near Yeavering, a landscape dotted with Anglo-Saxon settlements, the entire place is alive with spirits and stories just straining to be told.

People could not have been more helpful. We met first with Graeme Young at Bamburgh castle. Graeme is the archaeologist there and he gave me any number of wonderful tidbits.

When we’d finished up walking the ramparts and getting thoroughly soaked, Graeme invited Ron and me to join him and another archeologist, Kristian Pedersen, for lunch at the nearby Victoria Inn. Can’t tell you how welcome that cup of tea was. It also proved a most interesting couple of hours, as Kristian is an ex-paratrooper who served in Somalia and a man of considerable story himself – but they are his stories and not mine to tell.

On our final day before heading for Edinburgh, we went out to Yeavering, in the Cheviot Hills, the site of a great Anglo-Saxon palace, build in the shade of a huge dark hill on the top of which once stood the outline of an iron-age fortress. We met with Paul Frodsham, an archeologist who has written a number of books at the Red Lion Pub in nearby Wooler, and then drove the two or three miles to the place where King Edwin’s great compound one stood. You can learn more about this site here. The place was once called Ad Gefrin, which means At the Hill of the Goats, and although wild goats still live in the hills, and one actually came down to meet Paul one day, sadly none appeared for our visit.

It may not look from this photo as though there was much to see, and that might be true, if one were looking for the sort of tourist attraction that generally leads people to such places. It was just the hills and the plain, and the River Glen below, where Paulinus once spent 36 days baptising new Christians. However, I was filled with a sense of peace there, and an undeniable resonance – the sort of feeling which invites you to find a warm rock next to a gurgling stream and sit down and listen to the voices of the land for a while. And that’s what I did, for not nearly long enough.

The truth is that part of my heart (as the song goes) remains on the windy, sky heavy, sea-tossed land of Northumberland. It is also true that nearly everything I thought I would write about before I went on this trip has changed. That is what you have to be ready for, if you decide to let a story lead you, rather than trying to force a tale into a preconceived shape.

Part of me, I must admit, is nervous about the new direction for this book. I feel it has to be much smaller, more intimate, and more human in scale than the historical epic I first envisioned. I also fear I will let down some people I spoke to on my journey who had very set ideas about the way saints and places should be handled. But the first responsibility of any writer, I feel, is to be true to the voice that speaks from their soul, if you will. In other words, I can only write the tale of the characters who introduce to themselves to me as I walk along the road to meet them.

Tomorrow I’ll sit again in front of a blank page and begin, for the fifth time, this novel of a woman in the Anglo-Saxon era of Northumberland. We’ll see where it all leads. . .

Copyright 2015 Lauren B. Davis For permissions: laurenbdavis.iCopyright.com

Dear Lauren, I have very fond memories of being with you on this exciting trip up the east coast of England in 2008. It’s so inspiring to see how you’ve applied your many literary skills together with extensive research on the 7th century to produce your 7th book, which is your best yet!

And by the way, it was well worth it to find and be able to touch Hadrian’s Wall. with love, Ron

You do know, Ron, that you could have just told me this over the dinner table, don’t you? And of course, one can’t help but assume some bias on your part. 😉 But still, you do know I couldn’t have done it without you, yes? xoxo

This was absolutely wonderful! Can’t wait to start the book!

Great seeing you both looking so well and obviously enjoying and making the most of life!

Christine

It was lovely to see you, Christine. Thanks so much for coming to the launch. I hope you enjoy the book!

Hello Lauren. I just read through this yesterday. We have also visited many of the sites you mentioned. I wish I had seen the glass bird at York Minster. The beauty of the glass there is overwhelming. It seems this trip was crucial to your writing process. I hope to visit the Isle of Man, as part of the setting for my next book is there. My grandfather’s ancestors all came from there. I just had my daughter visit on my behalf, and she said that my mother, her grandmother, really belonged there. She has never seemed to fit anywhere, but my daughter felt that this island would have been a true home to her. I totally agree that some places call to us. When my daughter was searching for a flat in London, she ended up choosing a place on the very street her great-grandparents lived, over one hundred years ago. We didn’t know that until a cousin we visited in York mentioned it. She thought we knew. So strange. And when I visit Quebec, I never want to leave, though I was born in Alberta. But my father’s family lived there for 400 years. There is something in the DNA that calls to us. My mother says it is because we are like homing pigeons. Perhaps so.

I’m glad you posted your journey. It reminded me of many aspects of our travels in that region. In Whitby, there is a haunted house because parts of Dracula were set there. It was a hoot. Did you go perchance? So glad that all your experiences contributed to your successful project!

Hi Lisa, thanks for your comment. I didn’t go to that house in Whitby (although we saw it). But I’m quite sure it isn’t the only haunted house in Whitby!

Hi Lauren, it’s been a while but always enjoy reading you and thinking about you and your “Best Beloved”. It certainly sounds like you had a most wonderful journey, meeting kind and interesting people and viewing sites that you’ll never forget (especially that famous wall).

Hope to see you guys again someday.

Love from the Balcers

We’d love to see you as well. So sorry we couldn’t be with you to celebrate this summer!